Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

December 9, 2025 at 7:59 am in reply to: Post on “The Illusion of Perception (Saññā) – It Is Scientific Consensus” #55886

Lal

KeymasterIt is essential to realize that the types of gati leading to the birth of a pig (with ‘pig suddhāṭṭhaka’) are cultivated by a human in my above analysis.

- A human with ‘human suddhāṭṭhaka’ is born mainly via the cultivation of ‘human gati‘ by a human.

- In the same way, a Deva with ‘Deva suddhāṭṭhaka’ is born mainly via the cultivation of ‘Deva gati‘ by a human.

- In Paticca Samuppada, we analyze how different types of kamma cultivated by humans (with different types of gati) lead to various types of births.

December 8, 2025 at 2:07 pm in reply to: Post on “The Illusion of Perception (Saññā) – It Is Scientific Consensus” #55884Lal

KeymasterI am glad you asked the question. This must be fully understood, because it is a somewhat ‘twisted’ mechanism that comes into play. Let me explain it in a bit more detail for those who may not know about vanna rupa, sadda rupa, gandha rupa, rasa rupa, and photthabba rupa.

- Everything in the world is made of suddhāṭṭhaka (fundamental unit of matter in Buddha Dhamma). Suddhāṭṭhaka (“suddha” for “pure” or fundamental” + “aṭṭha” or “eight”) means a unit of matter consisting of eight fundamental entities (usually translated as the “pure octad,” for example, in Bhikkhu Bodhi’s book referenced in #1 of “The Origin of Matter – Suddhāṭṭhaka.” A suddhāṭṭhaka is made of eight dhātu: pathavi, āpo, tejo, vāyo, and vaṇṇa, gandha, rasa, oja.

- The mind creates four types of gati (pathavi, āpo, tejo, and vāyo) due to avijjā or ignorance. The other four types of gati of vaṇṇa, gandha, rasa, and oja arise due to taṇhā. These gati (arising in the mind) lead to the creation of corresponding suddhāṭṭhaka with eight components of fundamental matter (called dhātu) in the ‘external’ world (and also in the physical body and even the mental body consisting of hadaya vatthu and the five pasada rupa, which can be called ‘internal’).

- Different types of saññā arise in distinct species due to the matching of ‘internal suddhāṭṭhaka‘ and ‘external suddhāṭṭhaka.‘

- This is why, while rotten food tastes yucky to humans, it tastes great to pigs. Even though the rotten food (‘external suddhāṭṭhaka‘) are the same, the composition of ‘internal suddhāṭṭhaka‘ in pigs is very different compared to humans. That is why they taste the same thing differently than humans do. This is a critical point to understand. Don’t hesitate to ask questions if the point is not clear.

- This is also why this (distorted) saññā arises even in an Arahant. An Arahant will live the same body that he/she was born with. Those ‘internal suddhāṭṭhaka‘ in the Arahant‘s body do not change upon attaining Arahanthood. Thus, he will experience the world just as any other human.

- But the Arahant fully understands how the “subjective reality’ with distorted saññā arises via Paṭicca samuppāda. The bonds to the rebirth process (ten samyojana) have been removed from the Arahant‘s mind via several stages (Sotapanna, Sakadagami, Anagami). An Arahant fully understands and has fully verified the “objective reality” (paramattha) but will experience the “subjective reality” until the death of the physical body.

- One can become a Sotapanna by just understanding the basic idea. But a Sotapanna would still have the distorted (kāma) saññā. That second step of not attaching to kāma saññā is achieved at the Anagami stage. Then the distorted saññā associated with the rupa loka (jhāma saññā) and arupa loka (arupa samāpatti saññā) are removed at the Arahant stage.

- I can write a post to clarify this critical point. Please keep asking questions.

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterYes. “If avijjā conditions rāga, and rāga in turn conditions paṭigha, then ‘avijjā paccayā rāga’ and ‘rāga paccayā paṭigha’ should logically follow, even though I have not seen them stated explicitly.”

- That is true and is implied, even though it is not explicitly stated. It is to be understood.

- For example, in ‘kama loka,’ ‘kama raga‘ arises automatically due to avijja (which is not realizing that all ‘sensual pleasures’ arise due to ‘kama sanna.’) When one does not get to enjoy ‘sensual pleasures,’ paṭigha or anger arises. Thus, ‘kama raga‘ and paṭigha can be considered as the two faces of a metal coin. The metal in the coin itself is avijjā.

- When avijjā is removed, the coin disappears, and ‘kama raga‘ and paṭigha also disappear.

The following is not true: “Likewise, ‘viparita saññā paccayā avijjā/taṇhā’ should also hold, since viparita saññā is inherent in the physical body and cannot be prevented from arising.”

- Arahants also experience the viparita saññā. However, even though the viparita saññā is inherent in the physical body and cannot be prevented from arising, Arahants‘ minds do not attach to them. P.S. That is because avijjā has been eliminated from their minds.

- For example, they also see flowers of mind-pleasing colors and experience the sweet taste of honey. But since they have fully understood how that viparita saññā arises (via Paticca Samuppada), their minds do not attach to such experiences. This is the critical step of uncovering “dhamma cakkku‘ or the “wisdom eye.’

- I will write more about that in the next post.

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterYes.

- However, rāga and paṭigha arise due to avijjā. That is why “avijjā paccayā mano/vaci/kāya-saṅkhāra.”

- Again, avijjā does not manifest without a condition for it to arise. That condition is saññā. See “What Does “Paccayā” Mean in Paṭicca Samuppāda?“

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterYes, tanhā could be viewed as a generalisation of all the ways in which one could become attached, i.e. through greed, anger or ignorance.

- When ignorance (avijjā) is completely removed from a mind, tanhā is also removed. Avijjā and tanhā go together.

- Tanhā manifests as rāga, which is mainly kama rāga (tanhā for things in kama loka), rupa rāga (tanhā for jhānic pleasures in rupa loka), and arupa rāga (tanhā for arupa samāpatti pleasures in arupa loka).

- When avijjā is wholly removed, one becomes free of rebirths in all three loka.

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterTaṇhā means “getting attached.” The word taṇhā comes from “thán” meaning “place” + “hā” meaning getting fused/welded or attached (හා වීම in Sinhala). Note that “tan” in taṇhā is pronounced like in “thunder.”

- We can attach to things because we form a liking or dislike for them, or we are not aware of all the facts about them. Once attached, one takes actions that could be immoral.

- See, “Tanhā – How We Attach Via Greed, Hate, and Ignorance“.

Let us consider some simple examples to illustrate the concept.

- Attaching with a liking (lobha or greed) is easy to see. A lady sees a dress in a shop and decides to buy it. She gets attached to the dress.

- We also attach with a dislike/anger (dosa or patigha). A person walking on the street may see an enemy approaching; he may cross the road to the other side to avoid facing him. Another Example: Suppose person X is wrongly accused by person Y, and person X loses many relationships. Now, anger arises in person X’s mind whenever he thinks about person Y.

- We can also attach due to ignorance (avijjā) or not fully understanding the situation. In the last example above, another person, Z, may come to the wrong conclusion that person X is a bad person and avoid him. In a deeper level, we attach to things out of both greed and anger because we don’t fully understand the Four Noble Truths.

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterThe newest post in the Vietnamese Pure Dhamma website is the translation of “Nibbāna ‘Exists’, but Not in This World.”

- The translated post is at: Nibbana “Exists”, but Not in This World – Pure Dhamma

- If anyone who can read Vietnamese can provide feedback, the translators and I would appreciate such comments.

Lal

KeymasterHe is talking about words used in ancient times. I am not familiar with most of them. I don’t know whether those are correct.

- Regarding “atto” is applied as a suffix to living objects, I have not heard that.

- However, in some villages, “atto” is applied to a “person” (actually as “attā”; it is not pronounced the same way as ‘atta’ in ‘anatta’: ඇත්තා as in ‘මේ ඇත්තා’ or ‘this person’).

1 user thanked author for this post.

November 24, 2025 at 9:24 am in reply to: Post on Kāye Kāyānupassanā – Details in Satipaṭṭhāna #55756Lal

KeymasterAt the end of my above comment, I wrote the following:

Even though I was discussing attaining the Sotapanna stage, the process can also be used to cultivate Satipaṭṭhāna, as mentioned at the beginning of my comment.

- However, it may not happen in a few sittings. Furthermore, one needs to grasp the fundamentals necessary and also live a moral life, i.e., cultivate sila.

_______

1. Cultivation of Satipaṭṭhāna (to access the ‘kāma saññā free’ Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi) by a Sotapanna is a bit more involved than I implied above. There are suttās that describe the required steps in detail.

- Before getting into that process, I think it is beneficial for most people (who may be puthujjana or Sotapanna Anugāmi) to understand the critical foundations of the Buddha’s teachings.

- In particular, I think it is not enough to understand that cravings for ‘worldly pleasures’ must be given up to attain Nibbāna.

- It is easier to give up the cravings for ‘worldly pleasures’ if one understands that external sights, sounds, tastes, etc, actually do not deliver those ‘pleasures.’

- The ‘sense of a pleasure’ arises from saññā built into us (all living beings) and from our external environments via Paṭicca Samuppāda.

- That is why I keep working to explain that deeper aspect.

2. When that framework is understood, it becomes easier to attain the Sotapanna stage and also to cultivate Satipaṭṭhāna.

- One of the steps in cultivating Satipaṭṭhāna is to cultivate ‘Indriya bhāvanā‘ or the ‘Restrain of Sense Faculties.’ It is explained in the “Indriyabhāvanā Sutta (MN 152),” for example. Let me explain the key ideas in that sutta to give an idea of why that ‘solid foundation’ is critically important.

3. In the days of the Buddha, other teachers (such as Alara Kalama) also taught ‘Indriya bhāvanā.‘ We all know that our Bodhisatta learnt cultivation of anariya jhāna from yogis like Alara Kalama before attaining Buddhahood with his own efforts.

- Such yogis realized that attachment to sense pleasures leads to bad outcomes, and that even forcefully abstaining from them can lead one to transcend the ‘kāma loka‘ and enjoy ‘jhānic pleasures’ associated with the Brahma realms. To achieve that, they went deep into the jungles to avoid enticing sensory stimuli such as tasty food, luxury houses, and women. However, our Bodhisatta realized that such efforts yield only temporary solutions. Such yogis will be reborn in a Brahma realm, but they may still be reborn in the apāyās in the future, since they had not broken the samsāric bonds associated with kāma rāga.

- Those yogis did not know that the way to be permanently free of the ‘kāma loka‘ is to comprehend how we attach to such sensory pleasures via ‘distorted saññā‘, which in this case is ‘kāma saññā.’ When one fully understands that process, one can cultivate Satipaṭṭhāna to become permanently free of the kāma loka and attain the Anāgāmi state. That is one way to explain the ‘previously unheard teachings’ of a Buddha.

4. In the above sutta, Uttara, a pupil of the brahmin Pārāsariya (a yogi like Alara Kalama), came to the Buddha and asked how the Buddha teaches ‘Indriya bhāvanā‘ to the bhikkhus.

- The Buddha, in turn, asked Uttara how his teacher taught him the ‘Indriya bhāvanā.‘

- Uttara’s answer was what I explained in #3 above, i.e., to ‘stay away from such sensory pleasures’ or to live like a blind person (who would not see such attractive sights), a deaf person (who would not hear such attractive sounds), etc. One can do that by living deep in the jungles.

- Then the Buddha (@marker 2.8) tells Uttara, “In that case, Uttara, a blind person and a deaf person will have developed sense faculties without any effort.” Such people do not crave attractive sights or sounds while they are deaf, but in future lives (when they are born with eyes and ears) they will have those cravings. Until the ‘kāma rāga samyojana‘ is broken with wisdom, one is not free of rebirths in the ‘kāma loka.’

- Then the Buddha explained the correct way to control the sensory faculties. We will discuss that in the future. It involves understanding how the ‘kāma saññā‘ arises via Paṭicca Samuppāda.

- But first, it is critically important to understand the role of saññā in our built-in attachments to so-called ‘sensory pleasures.’

1 user thanked author for this post.

November 23, 2025 at 12:08 pm in reply to: Post on Kāye Kāyānupassanā – Details in Satipaṭṭhāna #55753Lal

KeymasterYes. Both following goals can be attained in focused formal meditation sessions: (i) Attaining the Sotapanna stage, and (ii) Cultivating Satipaṭṭhāna to enter the Satipaṭṭhāna Bhumi to attain higher magga phala.

- I discussed that in the post “First Stage of Ānāpānasati – Seeing the Anicca Nature of ‘Kāya’” in the following section:

__________

Attaining the Sotapanna Phala

12. Even though most people attained the Sotapanna stage while listening to a single discourse by the Buddha, attaining the Sotapanna phala moment can happen anytime, anywhere, while contemplating. Of course, one must have learned the necessary Dhamma concepts (especially the ‘anicca nature’ of the world) from a Noble Person (an Ariya).

- The “Vimuttāyatana Sutta (AN 5.26)” describes five ways of attaining magga phala: (i) while learning Dhamma from a Noble teacher, (ii) while the person himself teaches Dhamma to others, (iii) and (iv) while the person is contemplating in detail Dhamma concepts learned from a Noble teacher. and (v) while fully immersed in a meditation subject (samādhi nimitta). Note that (ii) and (v) hold only for a Noble Person attaining higher magga phala. The other three also hold for puthujjana striving for the Sotapanna stage.

- Therefore, what matters is grasping the relevant Dhamma concepts and breaking the respective saṁyojana.

- We can look at two accounts from the Tipiṭaka to verify the above. Venerable Koṇḍañña attained the Sotapanna phala moment while contemplating the Dhamma he learnt from the first discourse delivered by the Buddha. Another is that of Ven. Cittahattha attained the Sotapanna phala moment while walking to the monastery to become a bhikkhu for the seventh time; along the way, he reflected on the Dhamma he had learned and realized the Sotapanna phala. See “Four Conditions for Attaining Sotāpanna Magga/Phala.”

Setting Aside a Day for the Effort

13. Therefore, one could, in principle, attain the Sotapanna stage within an intensely focused effort within even a day.

- As we have discussed, it requires: (i) learning about the ‘anicca nature’ of the world from a Buddha or a true disciple of the Buddha (a Noble Person) and then (ii) fully comprehending it with wisdom.

- Those two steps are called ‘jānato‘ (come to know about) and ‘passato‘ (seeing the truth of that with ‘dhamma cakkhu‘ or ‘with wisdom’).

- See “‘Jānato Passato’ and Ājāniya – Critical Words to Remember.”

Uposatha Sutta

14. This is why it is customary in the Buddhist countries to allocate a day (usually the Full Moon Day each month) to focus on this objective. They usually observe the ‘eight precepts’ or even the ‘ten precepts.’

- They spend the day listening to discourses and engaging in Vipassanā.

- In the days of the Buddha, this was called ‘uposatha.’ It can also be done to attain higher magga phala for a Sotapanna.

- The Buddha explained to Visākhā how to practice the correct version of ‘uposatha‘ in the “Uposatha Sutta (AN 3.70).” Apparently, there were two other wrong versions practiced at the time.

- Note that ‘uposatha‘ is translated as ‘Sabbath’ in the English translation. In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath is a day set aside for rest and worship. That does not convey the meaning of Buddhist ‘uposatha.’

- The correct version of the ‘uposatha‘ description starts at marker 4.1.

________

Even though I was discussing attaining the Sotapanna stage, the process can also be used to cultivate Satipaṭṭhāna, as mentioned at the beginning of my comment.

- However, it may not happen in a few sittings. Furthermore, one needs to grasp the fundamentals necessary and also live a moral life, i.e., cultivate sila.

1 user thanked author for this post.

November 23, 2025 at 8:34 am in reply to: Post on Kāye Kāyānupassanā – Details in Satipaṭṭhāna #55745Lal

KeymasterGood questions.

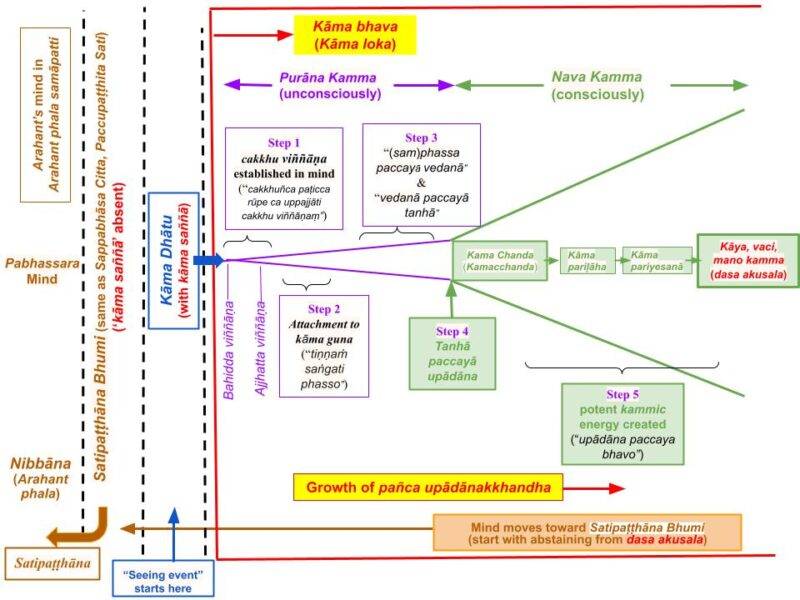

1. The word ‘anusotagāmi’ (‘anu sota gāmi’) means to stay engaged (‘gāmi’) with (“anu”) the flow of the rebirth process (‘sota’). Thus, the mind of an ‘anusotagāmi’ initiates a pañcupādānakkhandha process (equivalently, a Paṭicca Samuppāda process) upon receiving a sense input. The growth of the pañcupādānakkhandha is shown in the following chart.

- The growth of the pañcupādānakkhandha is from left to right in the above chart for an ‘Anusotagāmi.’ See “Growth of Pañcupādānakkhandha – ‘Anusotagāmi’.”

- When cultivating Satipaṭṭhāna (i.e., for a Paṭisotagāmi), one’s mind must move in the opposite direction. When someone sits down to cultivate Satipaṭṭhāna, their mind is already in the ‘expanded’ nava kamma stage. They must start moving the mind from the right to the left toward the Satipaṭṭhāna Bhumi.

- In that process, one encounters the ajjhatta kaya (with ajjhatta viññāṇa) before the bahiddha kaya (with bahiddha viññāṇa)

- Eventually, the mind overcomes the kāma saññā(temporarily) and jumps over to the Satipaṭṭhāna Bhumi.

- See #7 of “Paṭisotagāmi – Moving Toward Satipaṭṭhāna Bhumi and Nibbāna.”

_________

2. Tobias wrote the following in the second question/answer:

In which step does “Cakkhuñca paticca rūpe ca uppajjati cakkhu viññāṇaṁ” occur? Am I correct in understanding it as stated below?

– bahidda kaya: avijja paccaya sankhara, sankhara paccaya vinnana, vinnana paccaya namarupa

– ajjhatta kaya: namarupa paccaya salayatana, … vedana paccaya tanha

Is namarupa the “mind-made rupa” (rūpe) that develops with cakkhu to cakkhu vinnana?

The first part of bahidda kaya is processed by intact samjoyana (avijja and kamaraga), right? Gati are added via sanphassa?

Thus, the PS steps from avijja… to …tanha happen in a split second._____________

- Excellent! Yes. That explains the first part of the Paṭicca Samuppāda (PS) process. Let me provide a bit more information for the benefit of all.

- By the time cakkhu vinnana arises, both bahiddha and ajjhatta stages are complete, and cakkhu ayatana (with cakkhu vinnana) has arisen. That is Step 1 in the above chart. That also indicates PS processes from ‘“avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra’ through ‘nāmarūpa paccayā salāyatana.’

- Step 2 is ‘tiṇṇaṃ saṅgati phasso‘ in the chart, which corresponds to ‘salāyatana paccayā phassō‘ in PS. The verse ‘tiṇṇaṃ saṅgati phasso‘ appears in the “Chachakka Sutta (MN 148),” and is explained in #5 of “Indriya Make Phassa and Ayatana Make Samphassa.”

- Step 3 in the chart describes the PS steps of ‘phassa paccayā vēdanā, vēdanā paccayā taṇhā.’

- As you stated, all that will happen in the ‘anusotagāmi’ process within a split second. A mind will go through the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage in the blink of an eye.

- Once going through the ‘taṇhā paccayā upādāna‘ step, the mind can spend a lot more time engaging in akusala kamma, generating kammic energy. That is the ‘nava kamma‘ stage. This is where kammic energy for future rebirths/vipāka are generated via the ‘upādāna paccayā bhavō‘ step. Also see “Upādāna Paccayā Bhava – Two Types of Bhava.” This is Step 4 in the above chart. P.S. The ‘expanded cone’ for the ‘nava kamma‘ stage compared to the ‘smaller cone’ for the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage is meant to express this difference in kamma accumulation.

Anyone can ask follow-up questions. Tobias has pointed out some critical points.

1 user thanked author for this post.

Lal

KeymasterYes. May be it can be a bit refined as follows.

1. Anything that arises in the world (living beings and their environments) is a saṅkhata, meaning it has a finite lifetime and is subject to unexpected changes during that lifetime. That is because they all arise from kammic energies generated by the minds of living beings. Inert things in the environment arise due to collective kammic energies, while one’s own existences arise due to their own kammic energies.

- That is why nothing can be of nicca, sukha, atta nature. They are all of anicca, dukkha, anatta nature.

- That process is dictated by Paṭicca Samuppāda. Thus, nature runs based on the universal law of Paṭicca Samuppāda.

2. Five types of niyāma (utu, bīja, citta, kamma, dhamma) are not discussed in the Sutta Piṭaka or the Abhidhamma Piṭaka. At least I have not come across them. They appear only in late Commentaries.

- There is only one niyāma (dhamma niyāma) that is discussed. See “Uppādā Sutta (AN 3.126)“. That is Paṭicca Samuppāda.

- There is an old thread on the subject in the forum: “Five Niyamas-Does Every Unfortunate Event Always Have Kamma As A Root Cause?“

3. Living beings engage in akusala kamma (and generate kammic energies) by generating abhisankhara because of their efforts to enjoy ‘sensory pleasures.’

- However, all such ‘pleasures’ are mind-made (via Paṭicca Samuppāda). That means all ‘sensual pleasures’ in kama loka, ‘jhanic pleasures’ in rupa loka, and ‘arupa samapatti pleasures’ in arupa loka are all mind-made. We suffer in the rebirth process because we do not understand that all these ‘pleasures’ are like mirages! They feel like ‘pleasures’, but if you chase them, you will not find any lasting happiness.

- This is a bit complex subject that I discussed in several sections (in the following order): “Does ‘Anatta’ Refer to a ‘Self’?” “Sensory Experience – A Deeper Analysis” “Sotapanna Stage via Understanding Perception (Saññā)” “Buddha Dhamma – Advanced” “Meditation – Deeper Aspects” “Worldview of the Buddha” and “Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta – New Series”.

- This is why our actions seeking such ‘pleasures’ are all of anicca, dukkha, anatta nature. They are not only fruitless but also dangerous because they can lead to rebirths in the apāyās.

2 users thanked author for this post.

November 20, 2025 at 5:58 am in reply to: Gratitude post (or how Dhamma helped with my porn addiction) #55708Lal

KeymasterJittananto wrote: ” I recommend that everyone unfamiliar with this concept watch the sermon as a whole to gain a deeper understanding.”

1. I listened to the whole discourse last night.

- That discourse gives a superficial understanding of saññā (perception). By the way, the word ‘saññā‘ is not even mentioned.

- It does not provide “a deeper understanding.”

- So, I am not saying that discourse is useless, but it does not provide any additional information on what I am trying to convey.

2. You did not grasp that deeper meaning when you wrote the previous long comment either.

- That is why I wrote the following in response to it.

“You wrote: “Because of Ignorance (Avijja), we believe the Samsara is pleasurable, therefore we attach (Ragā) ourselves to the 31 realms.”

- Yes. We can say that avijja is the ignorance of the role played by the (distorted) saññā, which is ‘kāma saññā‘ in our kāma loka.

- Without colors, tastes, smells, etc. (generated via ‘kāma saññā‘), we would not crave anything in the kāma loka. Thus, ‘kāma saññā‘ is the trigger for our attachments.

- I tried to explain that in the post What Does “Paccayā” Mean in Paṭicca Samuppāda? “

__________

3. Anyway, I will write more on this critical issue when I start a new series on the pañcupādānakkhandha.

- I wonder how many people grasped the concept. Of course, not all participate in the forum.

- When people post discourses that are not really relevant to the point I am trying to make, it diverts the focus. Of course, I understand that everyone has good intentions.

- Buddha’s teachings are much deeper than many believe. Again, my goal is not a wider audience but to get at least a few to the Sotapanna stage.

November 19, 2025 at 5:57 am in reply to: Gratitude post (or how Dhamma helped with my porn addiction) #55698Lal

KeymasterWhere does the Thero talk about saññā?

- When you provide a link to a given subject, please point out the relevant timestamps.

November 19, 2025 at 5:39 am in reply to: Post on “Purāna and Nava Kamma – Sequence of Kamma Generation” #55697Lal

KeymasterTobias asked: “Why is a physical body necessary for distorted sanna and hence kamma generation?”

- A human gandhabba is the essence of a human. It has ‘distorted saññā‘ (i.e., kāma saññā).

- It is just that it cannot fulfil its desires for tastes, smells, and touches since it does not have a physical body.

- Since it does not have a physical body, it cannot engage in killing, stealing, or sexual misconduct. But even though it cannot speak out, it can still generate vaci kamma with vaci saṅkhāra. See #7 of “Correct Meaning of Vacī Sankhāra.” Even though it is unable to do the three types of kamma with the physical body, a gandhabba still generates the urge to engage in them, i.e., generate vaci saṅkhāra. Thus, it probably lives a frustrated life.

- Therefore, it can still generate kammic energies through vaci saṅkhāra and mano saṅkhāra. It is just unable to carry out some of the wishes.

I hope the above answers questions in DammaSponge’s mind. If not, feel free to ask any remaining questions.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

AuthorPosts