Writing Pāli words with the Latin script uses a convention adopted by the British Government in 1866. Unlike in English, the letters have a “one symbol – one sound” character. I call it “Tipiṭaka English convention” to differentiate it from writing in “Standard English.”

February 8, 2020; revised October 14, 2022; May 22, 2023; April 10, 2024

Background

1. Just three months after the Buddha’s Parinibbāna (passing away), the First Buddhist Council (Dhamma Sangāyanā) occurred. The leading disciples of the Buddha realized the importance of organizing the teachings of the Buddha, which had accumulated over 45 years. Organizing the material into “three baskets” (Tipiṭaka) was completed only at the Third Council held 200 years after the Parinibbāna of the Buddha.

- The material in the Tipiṭaka was transmitted verbally from one generation to the next over roughly the first four hundred years. It was only at the Fourth Council that the Tipiṭaka was written down.

- The Tipiṭaka (or the Pāli Canon) was written down in Matale, Sri Lanka, at the turn of the first century, 2000 years ago. Pāli is a spoken language and does not have a script. The Tipiṭaka was written in the Sinhala script.

- See details in “Preservation of the Buddha Dhamma.”

Writing Pāli Words in English – Different Convention

2. There are two specific issues in writing Pāli words in any language. Note that this does not include translation into English. It is about transliterating Pāli texts with the Latin (Roman) script. The Latin script is used here to transliterate (not translate) the Pali text. This enables people who are familiar with the Latin script (like English speakers) to read and pronounce Pali words. See “Pāli Words – Writing and Pronunciation.”

- First, Pāli is a phonetic language, meaning words must provide original sounds. Many words have their meanings explicit in the way they sound. See “Why is it Necessary to Learn Key Pāli Words?“

- However, in “Standard English,” the same letter combinations may yield different sounds. For example, “th” is pronounced differently in “them” than in “thief.” Therefore, writing in “Standard English” will lead to problems writing Pāli words.

- The second issue is that Pāli words written in “Standard English” become very long. I see many Sri Lankans writing “anicca” as “anichcha” (අනිච්ච in Sinhala) because that is how it is pronounced.

- We must adhere to the convention adopted by the Early Europeans (in the late 1800s) to have a standard pronunciation and to avoid words getting too long. First, let us discuss these two issues in some detail.

- Let us first address the “sound” issue.

English “th” Sound Depends on the Word

3. We know that “th” represents a different sound in the word “them” than in “thief.”

- A phoneme is the smallest contrastive segment in a language. In other words, they are the smallest building blocks that make the difference between two words. The term digraph describes a combination of two letters representing only a single phoneme.

- In words like them, father, and writhe, the digraph is th (voiced), and the phoneme is /t͟h/. This is the “ද” sound in Sinhala, as shown below.

- On the other hand, in words like thief, Catholic, and both, the digraph is th (voiceless), and the phoneme is /th/. This is the “ත” sound in Sinhala.

- Don’t worry about the above technical terms. The point here is that one MUST be aware of the correct “Standard English” when pronouncing those English words.

- That was one reason to adopt a new “Tipiṭaka English” convention. Now, let us discuss the second reason.

Pāli Words can become very long in “Standard English”

4. Now, let us see why the “Standard English” convention leads to long words written with the English (Latin) alphabet. Let us take a simple Pāli word, “citta.” In the original Tipiṭaka, it was written as “චිත්ත” in Sinhala.

The “ch” sound in English is seen, for example, in “china” and “chain.” It takes two English letters to produce the “ච” sound. In the same way, the “ත” sound requires two letters, “th,” in English as in “Theme” or “both.”

- Therefore, in “Standard English,” “චිත්ත” would be reproduced as “chiththa.” As you can see, it would take eight letters instead of five in “citta.”

- With more complex Pāli words, the corresponding “Standard English” reproduction would be cumbersome. That seems to be the second reason for using a different “Tipiṭaka English” convention; see below.

Evolution of “Tipiṭaka English”

5. When the early Europeans started writing the Pāli Tipiṭaka using the English alphabet (a Latin alphabet), they ran into the above two problems. They realized the necessity to represent the original sounds in an “unambiguous and efficient” way. To address the above issues, they adopted a new convention in the 1800s.

- We will call the convention they adopted “Tipiṭaka English.”

- That “Tipiṭaka English” convention is DIFFERENT from “Standard English.”

6. I came across an old book by James D’Alwis, published in 1870 (Ref. 1), that describes the historical process of cataloging the Pāli literature found in Sri Lanka (called Ceylon at that time.) The book is available on Amazon.

- The seed for the project was a request by a government agent in 1868 to the “Chief Translator to Government” to assist with a project in India to collect and compile Sanskrit literature.

- In 1869, the Chief Translator to the Government replied that nearly all Sanskrit manuscripts in Ceylon were “importations from India.” He suggested initiating a similar effort to collect and compile the Pāli and Sinhalese manuscripts in Ceylon would be worthwhile.

- That proposal was approved in early 1870. James D’Alwis, who had done some work on Pāli/Sinhalese literature and Buddhism, was selected to collect and compile such manuscripts mainly from Buddhist temples (“pansalas.)”

- Mr. D’Alwis was a civil servant of the British Government at that time. At that time, there was a concerted effort by the English civil servants to recover and preserve all ancient literature that they came across in Asian countries. See “Background on the Current Revival of Buddhism (Buddha Dhamma).”

- Dr. Malalasekera’s account confirms the above background in Ref. 2, pp. xv-xvii.

The Original Convention for “Tipiṭaka English”

7. The goal was to collect all Pāli manuscripts and write them with the English (Latin) alphabet. The early work by Mr. D’Alwis followed (as quoted from p. xxviii of the book) “the system sanctioned by Government in the Minute, which is published in the Appendix.”

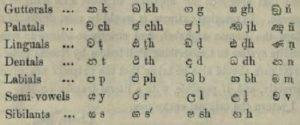

- A full page in the Appendix contains the complete alphabet of the Sinhala language (and the corresponding English script adopted). Download here: Complete Orthography – Sinhala to English

- That page (on p. 234 of the book) has the Sinhala alphabet and the Latin letters adopted to represent those sounds (adopted on August 28, 1866.) That was the first version of the “Tipiṭaka English” convention. As we will see below, one more change was adopted based on a recommendation by D’Alwis.

- It may be difficult to read that page. The following is an enlarged section containing the consonants.

Download here: Pāli Words – Sinhala to English Script – Consonants

- Now, let us discuss some of the adopted conventions in “Tipiṭaka English.”

Only “t” Represents the “ත” Sound

8. The letter “ත” in Sinhala represents the sound “th” in theme or north. But the “Tipiṭaka convention” is to use “t.”

- Therefore, “theme” in “ordinary English” becomes “teme” in “Tipiṭaka English.”

- The word “gati” is pronounced as “gathi,” where the sound “th” as in theme. But the “Tipiṭaka English” convention is to write as “gati.”

- The word “Tipiṭaka” also starts with the “ත” sound. In “Standard English,” it would be “Thipitaka.“

Anatta in “Standard English” would be “anaththa.”

- Therefore, words become significantly shorter with the “Tipiṭaka English” convention. With more complex words with the “ch” and “th” sounds, the corresponding English words can become very long.

Only “d” Represents the “ද” Sound

9. Another is the “ද” sound, pronounced like “this.” In “Tipiṭaka English,” the letter “d” represents the “th” sound in “this” or “that.“

- For example, the Pāli word “දස” in “Tipiṭaka English” is “dasa.” which needs to be pronounced like the “th” sound in “the” or “that.”

- Of course, the word “dasa” appears in “dasa akusala” for “ten immoral deeds.”

- More examples are sadda, hadaya, and Dēva.

The “ච” Sound In the Above Table is With “ch“

10. It is interesting to see that the above Table (in #7) has the “ච” sound represented with “ch” as in “Standard English.” Thus the decision to use “c” to represent the “ච” sound was made later.

- The text in D’Alwis’s book represented that “mixed convention.” On p. 136, for example, the name “Kacchchāna” appears. In modern texts, it is “Kaccāna.”

- The word “vivicchati” (විවිචිඡති in Sinhala) appears on p. 73 as “vivichchhati,” where “ch” represents the “ච” sound and “chh” represented the “ඡ” sound. We can see why they decided to make that change too!

- By the time “The Dhammasangani” by Edward Müller came out in 1885 (Ref. 3), they had adopted the current convention to use “c” to represent the “ච” sound.

Current Convention – Only “c” Represents the “ච” Sound

11. For example, the letter “ච” frequently appears in Pāli verses, and it has the “ch” sound (as in chai tea). In “ordinary English,” the Pāli word anicca (අනිච්ච) would be “anichcha.” You can see why that would lead to very long words in English. I used to do that too, and I still see some Sri Lankans writing words that way.

- Therefore, in almost all cases, a single English letter “c” represents the “ch” sound in “Tipiṭaka English.”

- Note that “chai tea” would be “cai tea” in “Tipiṭaka English”!

“Tipiṭaka English” Conventions Hold Everywhere

12. The “ත” sound is ALWAYS represented by “t,” and the following are some examples we use often.

- Atta, Anatta, gati, sōta, tanhā, tējō, Tilakkhana, Tisarana, āyatana

The “ද” sound is ALWAYS represented by “d” as in the following:

- Hadaya, sadda, dōsa, Deva, desanā, diṭṭhi, dukkha, dugati, pasāda

Finally, the “ච” sound is ALWAYS represented by “c” as in the following:

- Anicca, citta, cakkhu, cuti, paccayā, sacca, rūpāvacara, cētasika, cetanā

The above words are pronounced in the audio below:

Pāli Alphabet with Illustrations & subtitles

13. The following video could be very useful in learning the Pāli alphabet (in English.) Moreover, it provides excellent instructions on pronunciation.

REFERENCES

- James D’Alwis, “A Descriptive Catalogue of Sanskrit, Pāli, and Sinhalese Literary Works of Ceylon, Volume I” (1870)

- G. P. Malalasekera, “Pāli Literature of Ceylon” (2010 edition; first edition 1928)

- Edward Müller, “The Dhammasangani” (1885)

A few more essential features of the “Tipiṭaka English” convention are discussed in the next post, “Tipiṭaka English” Convention Adopted by Early European Scholars – Part 2.