Buddha Dhamma (Buddhism) is about much more than living a moral life. It is about eliminating future suffering without a trace.

Revised November 16, 2019; February 1, 2023; revised with new chart July 22, 2023

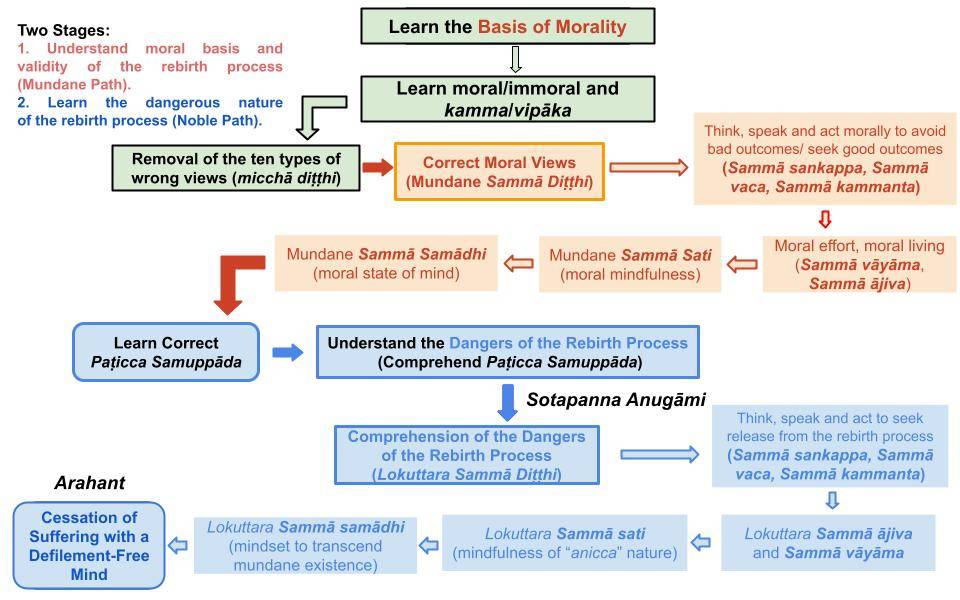

All Religions Are the Same?

1. When I hear the frequent statement, “All religions are the same; they teach you how to live a moral life,” I cringe. That is because I think about all those unaware of the Buddha’s unique message. In particular, this is the mindset of those who follow “secular Buddhism.”

- Most religions indeed teach how to live a moral life. And there is also evidence that atheists may be as moral as religious people are; see “Morality in everyday life-Science-2014-Hofmann“.

- However, Buddha Dhamma goes beyond that. The Buddha said no matter how well we live this life, that will not help us in the long term in the rebirth process.

- Any suffering one may experience in this life is nothing compared to the harsh suffering in some other realms in the rebirth process. Understanding that constitutes the first (mundane) path. The second, Noble Path, is followed to stop that harsher suffering permanently. Thus, the Buddha split the path to be followed into two paths.

Two Eightfold Paths

2. I have made a chart to illustrate the two types of Eightfold Paths explained by the Buddha:

Download/Print: “A. Buddha Dhamma – In a Chart.”

3. In the “Mahā Cattārisaka Sutta (MN 117),” the Buddha discussed that one must first complete the mundane eightfold path. That will remove the ten types of wrong views (micchā diṭṭhi) listed in #3 of the post “Maha Chattarisaka Sutta (Discourse on the Great Forty).

- After that, one needs to comprehend the Four Noble Truths, Paṭicca Samuppāda, and Tilakkhana (anicca, dukkha, anatta) to some extent to start on the Noble Eightfold Path. See “Paṭicca Samuppāda, Tilakkhana, Four Noble Truths.”

- Thus, one starts on the Noble Eightfold Path starting with lokuttara (transcendental) sammā diṭṭhi of a Sōtapanna (set of blue boxes in the chart). One has seen a “glimpse of Nibbāna,” i.e., one KNOWS that permanent happiness is not possible anywhere in the 31 realms and that whatever effort one makes to achieve such happiness is like chasing a mirage.

First, the Mundane Path

4. To reach a specific location, one must first find the path. When grasping a new concept, it is called “seeing with wisdom.” Before being able to “see” what is meant by Nibbāna (escape suffering in the rebirth process), one must first “see” or “be convinced” of specific essential criteria. For example, actions (kamma) have consequences (vipāka), there is a rebirth process, etc.

- Many Buddhists today believe they can make spiritual progress by following rituals. However, making progress on both paths requires “seeing with wisdom” (or “Dhamma cakkhu.“) Thus, each of the two paths starts with its version of sammā diṭṭhi.

- The “mundane Eightfold Path” is depicted by the set of boxes in red, starting with “mundane sammā diṭṭhi.” One would have that “mundane sammā diṭṭhi” when one removes doubts about the ten types of wrong views. See “Dangers of Ten Types of Wrong Views and Four Possible Paths.”

- The next box depicts mundane versions of sammā saṅkappa, sammā vācā, and sammā kammanta,” meaning “think, speak, and act morally to avoid bad outcomes/seek good outcomes”) and so on until “mundane sammā samadhi.”

- Most of these steps (not all) are in other religions and conventional or secular “Buddhism.” They advocate living a moral life (i.e., engaging in “good deeds” or “good kamma.”) That means understanding actions (kamma) have consequences (vipāka), the same as in Buddha Dhamma.

5. However, most other religions aim to gain a (permanent) heavenly life at death. While living a moral life can be conducive to getting a rebirth in a good realm, the Buddha taught that it will not be a permanent existence. That is the main difference.

- We create causes and conditions to bring new rebirths via our defiled actions, speech, and thoughts with greed, anger, and ignorance of the true nature of the world; they are all kamma. The point is that kamma (more precisely, kammic energies) lead to kamma vipāka (results of kamma.) “Good kamma” lead to rebirths in “good realms,” and “bad kamma” lead to rebirths in “bad realms.” We keep moving among the two types of realms, and that is the basis of the rebirth process. There is no end to it until we understand the deeper Buddha Dhamma.

- Stated simply, we can stop kamma bringing their vipāka by eliminating the conditions for such vipāka to take place, i.e., kamma vipāka are not pre-determined; see “What is Kamma? – Is Everything Determined by Kamma?“ One can begin to see the truth of that when one gets rid of the ten wrong views while on the mundane path. To comprehend that mechanism, one needs to understand Paṭicca Samuppāda, as discussed below.

What Is a “Good Rebirth”?

6. The joys of heavenly lives are highlighted in the distorted versions of “Buddhism” that are mainstream today. Sometimes one is encouraged to “enjoy such heavenly lives” before attaining Nibbāna.

- A phrase used by some bhikkhus in Sri Lanka goes as, “May you enjoy heavenly pleasures and then attain Nibbāna at the time of the Buddha Maitreya (next Buddha).” Why not attain Nibbāna in this life? Who is going to give guarantees that one will be born human during the time of the Buddha Maitreya?

- They don’t understand that anyone living today may not get an opportunity to be born human during the time of the next Buddha. Not surprising because they don’t understand the “anicca nature” of any realm in this world.

- That misconception in “Buddhism” arises because the rarity of a “good rebirth” has not been comprehended; see “How the Buddha Described the Chance of Rebirth in the Human Realm.” This is why the Buddha said, “No happiness can be found anywhere in the 31 realms” (the true meaning of anicca). I highly recommend “Nibbāna “Exists,” but Not in This World.”

The vision of the Noble Path – “No Permanent Good Existences”

7. Even if a heavenly rebirth is attained in the next life, a future rebirth in the four lowest realms (apāyā) cannot be avoided without attaining the Sōtapanna stage of Nibbāna.

- Until one comprehends Paṭicca Samuppāda, one will always value “sensory pleasures.” That holds for atheists as well as for theists. The latter also believe that future happiness is in permanent heaven (most religions) OR temporary happiness in heavenly worlds (traditional “Buddhists”). The difference between a traditional “Buddhist” and a Bhauddhayā (or a Noble Person or an “Ariya“) is discussed in “A Buddhist or a Bhauddhayā?“.

- One starts on the transcendental (lokuttara) or the Noble Eightfold Path when one comprehends the dangers of the rebirth process and BECOMES a Sōtapanna. See “Paṭicca Samuppāda, Tilakkhana, Four Noble Truths.”

- When one is starting to gain that understanding, one is called a Sōtapanna magga anugāmi or a Sōtapanna Anugāmi; see “Sōtapanna Anugami and a Sōtapanna.”

Two Types of “Sammā Diṭṭhi“

8. Note the difference in the box next to “sammā diṭṭhi” in the two cases. In the mundane path, “sammā saṅkappa, sammā vācā, sammā kammanta” are “moral thoughts, speech, and actions” intended to avoid bad outcomes and to seek good outcomes.

- In the Noble path, “sammā saṅkappa, sammā vācā, sammā kammanta” are “thoughts, speech, and actions” intended to stop the rebirth process. One would not do immoral things because there is “no point” in doing such things. One knows that such things are unfruitful and dangerous in the long run because of their bad outcomes, i.e., they lead to “bad rebirths.”

- And one becomes more compassionate towards all living beings (not just humans) because one can see that each living being suffers because of ignorance of the Buddha’s key message. Any living being in any realm (including the apāyās) had been born human many times in the “beginningless rebirth process.”

Mundane Eightfold Path

9. The above-described unique message of the Buddha went underground only 500 years after the Buddha; thus, only a relatively few have been able to make real progress toward Nibbāna for two thousand years. What is conventionally practiced today is just this mundane Eightfold Path. This is what we call “Buddhism” today. See “Counterfeit Buddhism – Current Mainstream Buddhism” and “Anicca, Dukkha, Anatta – Distortion Timeline.”

- That superficial or “secular” Buddhism is not that different from what is advised by most other religions. Thus, it is easier for people to resonate with the mundane concepts in “Buddhism.” Sammā Diṭṭhi, for example, is considered the “correct vision” of “how to live a moral life.”

- Of course, that is the first necessary step. That will help one to be able to experience the benefits of moral behavior (even in this life as a “nirāmisa sukha“; see “How to Taste Nibbāna“) and then comprehend anicca, dukkha, anatta, and embark on the Noble Eightfold Path to stop even a trace of suffering in Nibbāna.

Noble Eightfold Path

10. One has the ability to become a Sōtapanna Anugāmi (the path to the Sōtapanna stage) anytime after getting to the “red boxes,” i.e., while one is on the mundane Eightfold Path. Of course, one MUST learn the correct version of Buddha Dhamma or Paṭicca Samuppāda.

- Anyone at or above the Sōtapanna Anugāmi stage is a Bhauddhayā. See “A Buddhist or a Bhauddhayā?” Even though not in the Tipiṭaka, sometimes the word “Cūla Sōtapanna” (pronounced “chūla sōtapanna”) is also used to describe a Sōtapanna Anugāmi.

- The key is comprehending the “true nature of this world of 31 realms,” Buddha described. That says it is impossible to achieve/maintain anything that can be kept to one’s satisfaction (anicca.) Thus one gets to suffer (dukkha), and thus, one is truly helpless in the rebirth process (anatta). This realization is like lifting a heavy load that one has been carrying, the first taste of Nibbāna.

- This “change of mindset” for a Sōtapanna is PERMANENT, i.e., it will not change even in future rebirths. One has attained an “unbreakable” level of confidence (saddhā) in the Buddha, Dhamma, and Saṅgha.

Material Phenomena Arise After Mental Phenomena

11. Buddha Dhamma focuses on the mind, as stated in the first Dhammapada verse, “Manōpubbangamā Dhammā..” Almost all fundamental concepts in Buddha Dhamma involve “mental entities” and not “material entities.” For example, when referring to a “rupa,” it is about the “mental image” that arises in the mind; see “Difference Between Physical Rūpa and Rūpakkhandha.” Thus when the Buddha states, “Rūpaṁ, bhikkhave, aniccaṁ,” that refers to the “mental image of a rupa that arises in mind” (it is of “anicca nature”) and NOT merely to an external rupa.

- Most people incorrectly interpret the verse “Rūpaṁ, bhikkhave, aniccaṁ” to mean an external rupa (like that of a person or a tree) is “impermanent.” It is the tendency to adopt such “mundane interpretations” that led to the distortion of Buddha Dhamma only 500 years after the Buddha; see “Anicca, Dukkha, Anatta – Distortion Timeline.”

- A person or a tree arises based on mental entities arising in the mind: “Manōpubbangamā Dhammā..” The mind creates “dhammā” that gives rise to all material phenomena; also see “Dhamma and Dhammā – Different but Related.” We will discuss that issue in detail (again, with a different approach) in upcoming posts.

- When one becomes a Sotapanna, one breaks three of the ten “mental bonds” (saṁyojana) that bind one to the rebirth process. It is a permanent change of mindset.

- A Sōtapanna can follow the rest of the seven steps in the Noble Eightfold Path even without help from others. Thus one will attain the following three stages of Nibbāna (Sakadāgāmi, Anāgāmi, Arahant) successively by following those steps.