Assāda (sense pleasure) starts with ‘kāma saññā’, triggering a ‘trace of liking‘ (manāpa) and grows rapidly to a strong ‘sukha vedanā’ that a puthujjana consciously experiences after the mind goes through many ‘re-attaching steps’ within a split second. Thus, the ‘pleasure’ (assāda) experienced by a puthujjana with ‘kāma saññā’ is incomparably stronger than the ‘trace of liking’ (manāpa) experienced by an Arahant.

February 21, 2026

Effect of ‘Kāma Saññā‘ – Difference Between a Puthujjana and an Arahant

1. I have explained in many posts that a puthujjana (a human not exposed to Buddha Dhamma) or an Arahant experiences the same ‘kāma saññā‘ with a sensory input.

- Anyone born with a human body would automatically experience that ‘kāma saññā‘, providing a subtle ‘sense of liking.’ The Buddha called it ‘manāpa.’ They all experience the red color of an apple and its sweet taste, both of which are ‘mind-made perceptions.’ See “Human Life is Unlivable in a ‘Colorless’ World.”

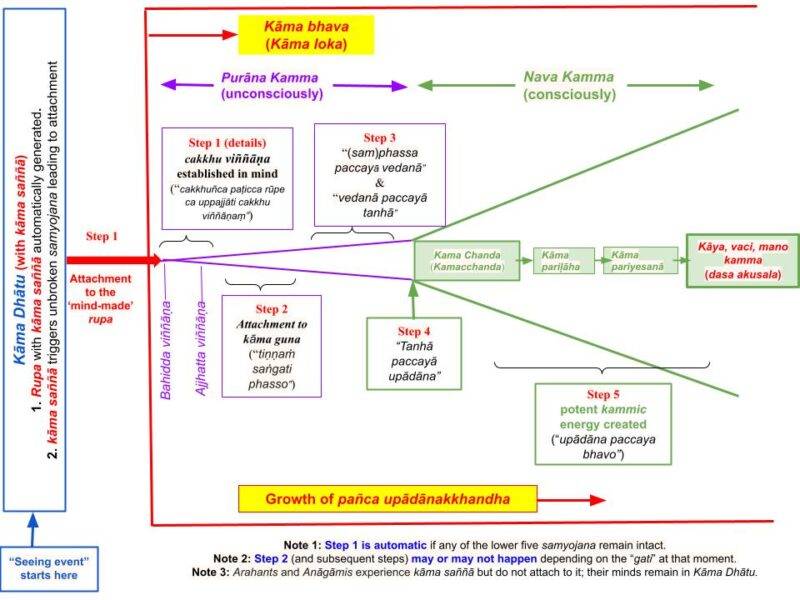

- The mind of a puthujjana (with all ten saṁyojana intact) will attach to that kāma saññā instantly, and their minds automatically move to ‘kāma loka.’ See the chart below.

- On the other hand, an Arahant’s mind (with all saṁyojana broken) would not move to ‘kāma loka,’ i.e., their minds do not attach to that initial ‘manāpa‘ or a ‘trace of sukha.’ Thus, the mind of an Arahant will never be defiled even to the slightest degree at any time.

- Even an Anāgāmi‘s mind will not move to ‘kāma loka‘ because they have also eliminated the five saṁyojana relevant to kāma loka. However, their mind will still attach to ‘jhāna saññā‘ or ‘arupa samāpatti saññā‘ and move to ‘rupa loka‘ and ‘arupa loka‘ respectively.

‘Manāpa/Amanāpa‘ and ‘Sukha/Dukha‘ Vedanā

2. The ‘kāma saññā‘ from some sensory inputs initiates a ‘trace of dislike‘ (amanāpa) in a puthujjana or an Arahant. An example is the taste of rotten food. It may lead to a strong ‘dukha vedanā‘ in a puthujjana, while an Arahant‘s mind remains at the amanāpa stage.

- Even Arahants experience “manāpa/amanāpa” or a sense of “like/dislike” generated by the “distorted saññā.” See “Nibbānadhātu Sutta (Iti 44)“: “Tassa tiṭṭhanteva pañcindriyāni yesaṁ avighātattā manāpāmanāpaṁ (“manāpa/amanāpa“) paccanubhoti, sukhadukkhaṁ paṭisaṁvedeti.” The English translation there is correct: “Their (Arahants‘) five sense faculties still remain. So long as their senses work, they continue to experience the agreeable and disagreeable, to feel pleasure and pain.” Also, note that “sukhadukkha” (sukha and dukkha) means “pleasure and pain” here refers to ‘body touches,’ which an Arahant feels too; see #12 below.

- We will focus on the ‘manāpa‘ aspect for the rest of the post.

Puthujjana‘s Mind Magnifies the ‘trace of liking‘ (Manāpa) to Increasing Levels of ‘Assāda‘

3. Now, the next key point is the following. The initial ‘trace of liking’ (manāpa) experienced with the ‘kāma saññā‘ for a puthiujjana may grow tremendously to a ‘strong sukha evdana‘ (assāda) by the time they become aware of it.

- The mind of a puthujjana will keep attaching to an enticing sensory input in many steps. Those steps in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage occur unconsciously, i.e., a puthujjana would not even be aware of them. Those steps are discussed below in #9.

- It is only after the mind is well into the ‘nava kamma‘ stage (which also has several steps where the ‘sukha vedanā‘ gradually increases) that a puthujjana becomes aware of the already intensified ‘sukha vedanā‘ due to the sensory input.

- Even for a puthujjana, assāda in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage is much weaker than in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage. When a puthujjana learns Buddha’s teachings, at some point, he/she becomes a paṭisotagāmi (“Paṭisotagāmi – Moving Toward Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi and Nibbāna“), and the mind reaches the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, where it experiences the ‘lower level of assāda‘. That is when a Sotapanna Anugāmi can overcome assāda and attain the Sotapanna phala moment.

- That is why one cannot effectively meditate on the ‘anicca nature’ while still in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage! By that time, the attachment to the ‘kāma saññā‘ would have become too strong to overcome.

It is Essential to Understand the ‘Steps of Mind-Contamination’

4. Therefore, comprehending the details of ‘mind contamination’, starting with the ‘kāma saññā‘ and proceeding through the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage to the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, is highly beneficial, even to attain the Sotapanna stage.

- It will help one see the steps necessary to go ‘backward’ and reach the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, where the strength of assāda is weak enough to overcome.

- Briefly, those retracing steps are: (i) abstain from generating new potent kamma (kāya, vaci, and mano kamma) in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, (ii) control one’s senses (indriya saṁvara) so that the mind does not get to the ‘taṇhā paccayā upādāna‘ step in Paṭicca Samuppāda, (iii) contemplate on the details of the initial steps of ‘mind contamination’ in the steps of the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage.

- Those steps must be fulfilled without interruptions, so that the mind can move progressively toward the less-contaminated ‘purāna kamma‘ stage. Thus, one must allocate at least several hours continuously to the effort to overcome the ‘kāma saññā.’ See #5 below for details.

- Then at some point, the mind will overcome the ‘kāma saññā‘ and jump over to ‘Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi.’ See “Overcoming Kāma Saññā – Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi or Jhāna.”

Setting Aside a Day for the Effort

5. This is why it is customary in the Buddhist countries to allocate a day (usually the Full Moon Day each month) to focus on this objective. They usually observe the ‘eight precepts’ or even the ‘ten precepts.’

- They spend the day listening to discourses and engaging in Vipassanā.

- Obviously, this forces them to abstain from akusala kamma, thereby preventing the mind from entering the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, and also to maintain indriya saṁvara.

- As they keep the mind focused on discourses and Vipassanā throughout the day, the mind gradually starts moving through the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage toward the Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi. Initially, they may gradually move toward the Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi while still in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage as a ‘Sotapanna Anugāmi.’

- At some point, with sustained effort, they may be able to overcome the ‘kāma saññā‘ and enter the ‘Satipaṭṭhāna Bhūmi‘ for the first time! That is when one attains the Sotapanna phala.

- Of course, some people may attain the Sotapanna phala without knowing the steps, by comprehending the ‘anicca nature’ of rūpa, vedanā, saññā, saṅkhāra, and viññāṇa (i.e., pañca upādānakkhandha). But the mind would still go through those steps, knowingly or unknowingly.

Uposatha – A Day Dedicated to the Practice

6. In the days of the Buddha, this practice of spending a day for meditation was called ‘uposatha.’ It can also be done to attain higher magga phala for a Sotapanna.

- The Buddha explained to Visākhā how to practice the correct version of ‘uposatha‘ in the “Uposatha Sutta (AN 3.70).” Apparently, there were two other wrong versions practiced at the time.

- Note that ‘uposatha‘ is translated as ‘Sabbath’ in the English translation. In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath is a day set aside for rest and worship. That does not convey the meaning of Buddhist ‘uposatha.’

- The correct version of the ‘uposatha‘ description starts at marker 4.1.

Attaining Magga Phala

7. The “Vimuttāyatana Sutta (AN 5.26)” describes five ways of attaining magga phala: (i) while learning Dhamma from a Noble teacher, (ii) while the person himself teaches Dhamma to others, (iii) and (iv) while the person is contemplating in detail Dhamma concepts learned from a Noble teacher. and (v) while fully immersed in a meditation subject (samādhi nimitta). Note that (ii) and (v) hold only for a Noble Person attaining higher magga phala. The other three also hold for puthujjana striving for the Sotapanna stage.

- Therefore, what matters is grasping the relevant Dhamma concepts and breaking the respective saṁyojana.

- We can look at two accounts from the Tipiṭaka to verify the above. Venerable Koṇḍañña attained the Sotapanna phala moment while contemplating the Dhamma he learnt from the first discourse delivered by the Buddha. Another is that of Ven. Cittahattha attained the Sotapanna phala moment while walking to the monastery to become a bhikkhu for the seventh time; along the way, he reflected on the Dhamma he had learned and realized the Sotapanna phala. See “Four Conditions for Attaining Sotāpanna Magga/Phala.”

- Even though most people attained the Sotapanna stage by listening to a single discourse by the Buddha, the Sotapanna phala moment can occur anytime, anywhere, while contemplating. Of course, one must have learned the necessary Dhamma concepts (especially the ‘anicca nature’ of the world) from a Noble Person (an Ariya).

Steps in the Increase of Assāda With Increasing Mind-Contamination

8. Now, let us return to our discussion of the mind-contamination steps, which were discussed in many posts, including “Overcoming Kāma Saññā – Satipaṭṭhāna Bhumi or Jhāna.”

- The following chart is from #2 of that post (second chart). It will help clarify the steps discussed in #9 below.

Download/Print: “Growth of Pañcupādānakkhandha“

Saṅkappa, Sara Saṅkappa, and Mano, Vaci, Kāya saṅkhāra

9. The ‘mind-contamination’ does not happen in ‘one shot.’ It happens via many steps, even though it can happen within a split second! The following are the three major steps (corresponding to the four steps in the above chart; the same type of ‘sara saṅkappa‘ arises in Step 3 as in Step 2):

- Step 1: Attachment to ‘manāpa’ leads to ‘saṅkappa‘: The initial mind-contamination is triggered by the ‘kāma saññā‘ in the ‘kāma dhātu‘ stage, giving rise to only a ‘manāpa‘ (‘trace of liking‘) as the very early stage of a ‘sukha vedanā.’ That automatically gives rise to ‘kāma saṅkappa‘ in the mind of a puthujjana. This is where ‘kāma rāga‘ arises (it is the ‘saṅkapparāgo purisassa kāmo‘ step; see Ref. 1). Contrary to what many believe, ‘kāma rāga‘ is very weak. It arises at the beginning of the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage. It will grow into ‘kāmacchanda‘ (a much stronger form) if the mind contaminates further in the following steps.

- Once entering the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, the mind of a puthujjana quickly goes through the ‘bahiddha viññāna‘ and reaches the ‘ajjhatta viññāna.‘ Even in these steps, the mind generates more ‘saṅkappa,’ and further defiles itself.

- Step 2: Attachment to ‘kāma guṇa’ leads to ‘sara saṅkappa‘ and ‘gehasita somanassa‘: In the middle of the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, the mind generates ‘cakkhuviññeyya rupa‘ and if those have sufficient ‘kāma guṇa‘ (based on the mindset at that moment), that will generate ‘sara saṅkappa‘ (sometimes just called ‘gehasita sara saṅkappa‘), and these are stronger than ‘saṅkappa‘ that led to the ‘bahiddha/ajjhatta viññāna.‘ The ‘sukha vedanā‘ intensifies to ‘gehasita somanassa‘ at this stage, i.e., assāda grows further.

- Step 4 (in the chart): The ‘taṇhā paccayā upādāna‘ leads to the start of accumulating potent kamma via mano, vaci, kāya sankhara, and ‘assāda‘ consciously experienced: Then, once in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, mind contamination is much stronger with mano, vaci, and kāya saṅkhāra responsible for mano, vaci, and kāya kamma that can bring vipāka even in future lives. The ‘mind-pleasure’ (somanassa vedanā) generated in this stage is stronger than the ‘gehasita somanassa‘ generated in Steps 2 and 3. That assāda can grow even stronger if the mind ‘really gets into it.’

- Don’t worry about not knowing all those terms. I will gradually introduce them as we proceed. I am truly amazed by the depth of these teachings! The point is that the ‘assāda‘ felt by a puthujjana is much stronger than the ‘manāpa‘ experienced by an Arahant. A puthujjana is not only not aware of the intermediate stages, but also does not experience them; they only experience the ‘assāda‘ generated in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage (strong somanassa vedanā)!

10. The ‘expanding cones’ in the above chart are only to be taken as guides. They indicate that the mind becomes ‘slowly contaminated’ in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, and that contamination accelerates in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage.

- The ‘assāda‘ also increases slowly in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, and accelerates in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage.

- Correspondingly, ‘kamma generation’ increases slowly (via saṅkappa and sara saṅkappa) in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, and accelerates in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage with potent mano, vaci, and kāya saṅkhāra.

- Thus, assāda (mind-made pleasure) and kamma accumulation (via attachment) feed on each other. Both grow within an instant in the ‘purāna kamma‘ stage, even without one being consciously aware of it.

Mind-Made ‘Samphassa-jā-Vedanā‘ Contribute at Each Step

11. The important point is the following: The strength of kamma accumulation, as well as the vedanā experienced (via samphassa-jā-vedanā‘ generation), increases at each step of mind contamination. It starts at the ‘manāpa‘ stage, goes through the ‘gehasita somanassa‘ stage, and, for those ‘enticing sensory inputs,’ gets to the highest ‘somanassa‘ stage after reaching the ‘nava kamma‘ stage.

- The initial ‘trace of liking‘ (manāpa) arising with the ‘kāma saññā‘ is the initial ‘vedanā‘ experienced. Here, mind contamination does not occur, but it is still called ‘samphassa.’ It is likely to be referring to ‘contact with saññā‘ (definitely not contact with ‘san‘ or ‘defilements’).

- That interpretation is verified in the Sūciloma Sutta. Once, a yakkha named Sūciloma came to harass the Buddha. He went to the Buddha and leaned against the Buddha’s body, and the Buddha pulled away. Sūciloma asked, ‘Are you afraid of me, ascetic?’

- The Buddha replied that he is pulling away only because the contact of Sūciloma was not pleasant (‘api ca te samphasso pāpako‘): “Sūciloma Sutta (SN 10.3).” Note also that ‘pāpako‘ only means ‘lowly/unpleasant‘ and is not related to ‘pāpa kamma.‘

‘Kāma Assāda‘ of a Puthujjana and ‘Manāpa‘ of an Arahant

12. Therefore, for a puthujjana, even though the ‘kāma saññā‘ triggered only ‘manāpa,‘ it leads to many more steps of ‘samphassa-jā-vedanā‘ or ‘vedanā generated via samphassa.’ That samphassa-jā-vedanā becomes increasingly stronger with subsequent saṅkappa and sara saṅkappa. They are strongest for mano, vaci, and kāya saṅkhāra generated in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage.

- Thus, ‘manāpa‘ of a puthujjana tiggers ‘kāma saṅkappa‘ at the very early stage. As more saṅkappa are generated, assāda increases too.

- Assāda becomes stronger with ‘sara saṅkappa‘ that arises if the mind attaches with kāma guṇa to trigger ‘kāmacchanda‘ after the ‘ajjhatta viññāna‘ stage.

- If the mind reaches the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, it begins to consciously focus on sensory input. Thus, ‘kāma assāda‘ becomes even stronger. This is when a puthujjana becomes aware of ‘kāma assāda.‘

- Now, we have a clear idea of the vast difference between the ‘kāma assāda‘ experienced by a puthujjana and the slight liking (manāpa) experienced by an Arahant due to the same sensory input.

‘Amanāpa‘ Due to an Injury Is Strong

13. An exception to the above is the initial ‘amanāpa‘ felt at the ‘kāma dhātu‘ stage due to an injury or a sickness. It is easy to visualize it with an injury. Yes, the ‘pain’ of an injury arises from saññā generated by the nervous system.

- Compared to the ‘sadda saññā‘ (with music) brought in via the ears (and other types of saññā), the ‘poṭṭhabba saññā‘ (body ‘touches’) is generated via the nervous system that runs under the skin. When you cut a finger, for example, the body (more correctly, the mind) generates a ‘painful feeling (poṭṭhabba saññā) to warn you about the injury. It is a good thing, because otherwise, you may bleed to death if unaware of it. Some, in rare cases (due to kamma vipāka), do not feel that saññā, and it can be dangerous.

- Unlike the weak, ‘manāpa/amanāpa‘ experienced with other physical senses, this ‘amanāpa‘ is strong. Both a puthujjana and an Arahant would experience similar ‘dukha vedanā‘ due to an injury. An Arahant would also feel the ‘sukha vedanā‘ of a luxurious bed, generated via the nervous system.

- However, a puthujjana generates more ‘dukha vedanā‘ (in the ‘nava kamma‘ stage) by worrying about the initial automatic ‘dukha vedanā‘ due to the injury. In contrast, that second type of samphassa-jā-vedanā is absent in an Arahant. This is explained in the “Salla Sutta (SN 36.6).”

Life Will Be Unlivable If Some ‘Saññā‘ Are Not Built-In to Us

14. The discussion in #13 explains why life would be unlivable if our bodies/minds do not provide certain saññā.

- We discussed that detail, focusing on the ‘color saññā‘ in the post, “Human Life is Unlivable in a ‘Colorless’ World .”

- In the same way, nature helps us avoid eating rotten food by providing a ‘yucky taste’ for rotten food. We can automatically detect a gas leak by smelling the gas. In the above discussion, we can avoid bleeding to death by taking care of a wound; we may not notice the wound if it did not cause the saññā of ‘pain.’

- In more subtle cases, we automatically realize that it is time to eat or to go to the bathroom; those are also saññā.

- Therefore, we must learn to live within the ‘mundane reality,’ while comprehending the ‘ultimate reality.’ See #14 of “Sakkāya Diṭṭhi and ‘Mind-Made Rūpa’.”

References

1. See “Nasanti Sutta (SN 1.34).” As stated in the previous verse (‘Na te kāmā yāni citrāni loke‘ ), ‘The world’s pretty things aren’t sensual pleasures.’ There are no ‘pretty things’ in the world, ‘sensual pleasures’ are perceptions made up in the mind: “Rūpa Samudaya – A ‘Colorful World’ Is Created by the Mind” and “Human Life is Unlivable in a ‘Colorless’ World.”