Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

December 11, 2024 at 12:20 pm in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52858

pathfinder

ParticipantThere is also another meaning of Jāti in that post:

8. When one gets deeper into Buddha Dhamma, one can see that everything in this world is “born” due to causes and effects, i.e., Paṭicca Samuppāda. For example, a tree is born out of a seed. A car is “born” in a factory. Paṭicca Samuppāda can describe all those.Do you think the jāti, jāra, maranaṃ of things outside of us is applicable in the Noble Truths as well? Eg jāti, jāra, maranaṃ of a car, a tree etc. Eg the Jāti of a painting does not matter to someone who is blind, but it does for someone who likes/ dislikes paintings and when they see it. The Jāti of a Buddha brings joy to many beings. The Venerable in Amin’s video also gave an example – the death (maranaṃ) of Bin Laden brought americans joy, but suffering to the Talibans.

Pathfinder wrote: “Jati itself is not suffering, but our attachment to it causes suffering.”

Lal: That is not correct. Any and all types of jati embed suffering.That makes sense, all Jāti embed suffering when we think of Uppatti Paṭicca Samuppāda jāti and Idappaccayātā Paṭicca Samuppāda jāti. It may be a bit different when we think about jāti, jāra, maranaṃ outside of us (with the example I gave about the painting and Bin Laden)

December 11, 2024 at 7:06 am in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52853pathfinder

ParticipantI only intended to share another way of interpreting. I apologise if I brought anyone confusion, but I want to reiterate that the end conclusion is the same. It is because it is not possible to find a world where we will never experience disliked jāti, disliked jāra, disliked maranan because of the anicca nature of this world, that we have to find a solution to this. And the cause of disliked jāti, disliked jāra, disliked maranan, is tanha (second truth). Without tanha, will we find things likeable and dislikeable in the first place?

Amin has also shared a sermon with another interpretation of “p” = attachment. So Jatipi dukkha means attachment to Jati is dukkha. It is also something to contemplate about. Jati itself is not suffering, but our attachment to it causes suffering. We too can come up with end conclusion that the cause of suffering is from attachment.

From this, I wanted to ask if Jati in the first noble truth refers to all 3 kinds of Jati described in Jāti – Different Types of Births nameley 1) birth of being, 2) brith during lifetime, 3) birth of everything else in the world. If I am not wrong, for the posts about first noble truth on this site, the “birth of being” is the main definition used, but I wonder if you would agree if the second and third meaning also applies.

December 10, 2024 at 7:45 pm in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52849pathfinder

ParticipantLal:All jati are undesirable. That is the explanation.

That is not how Thero explains it. At 23.02, he says “Can the likable and preferred (priya manāpa) nature of arisings (jāti) be considered as suffering? They are not. It is to this likeable and delightful nature the world-beings are attracted to. “Jāti api dukkha – jātipi dukkha)”

Here it is clear that he is saying not all jāti is dukkha. This is why he had to clarify that only Jāti api (disliked jati) is dukkha (23.15)

He also says the same for marana. We cannot translate maraṇampi dukkhaṁ as death is suffering, because not all death is suffering. He elaborates (30.54) “We welcome the demise/ death (‘marana’) of disliked and afflictive arisings/ manifestations/ things (jāti). That would certainly be a pleasant experience. How can it ever be suffering? We need to be truthful in understanding Dhamma, without deceiving ourselves”

Again he has to clarify (31.18) “Maranam api dukkha” means disliked demise/ death is suffering.

December 10, 2024 at 1:48 pm in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52833pathfinder

ParticipantI am not focusing on sabbe sankhara dukkha, but rather, his explanation of the first noble truth. You are right in that there is nothing new in his explanation of sabbe sankhara dukkha – we carry out sankhara and put in a lot of effort to achieve desirable things, but it is concealed by the likeable things, since we see them as worthy. I quote from the sermon (16.01) – “Is it fun to be working hard with the sweat running down your face? But that suffering gets concealed with one thing for which the worldly beings would keep on striving.”

What i found intriguing is this (23.20) – jātipi dukkā does not mean “jati too is suffering”. Rather, it is Jāti api dukkhā” shortened to “Jātipi dukkhā”. He used “Api iriyāva” – Apriya meaning disliked. So “jati api dukkha” means disliked arisings is dukkha.

I have not come across any interpretation like this before.

December 10, 2024 at 12:02 pm in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52831pathfinder

ParticipantAh yes, my previous understanding of dukkha sacca before this sermon is that there is much suffering associated with the rebirth process, because they always come with decay and death. The dukkha in Saccavibhaṅga Sutta is an inevitable product of the rebirth process. There is not just physical but mental pain (yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ) in the rebirth process.

December 10, 2024 at 10:18 am in reply to: Sermon by Waharaka Thero on “Noble truth of suffering” #52829pathfinder

ParticipantLal: “Sabbe sankhara dukkha” means “All sankhara dukkha.” It does not say “everything” is dukkha.” So, there is nothing “new” there.

That’s right, adding it there as a marker since it provides good elaboration.

Lal: What do you understand by “dukkha?” Is it the feeling of “dukkha vedana“?

I understand that dukkha can be a characteristic, as pointed out in Dukkha in Tilakkhana Is a Characteristic – Not Dukkha Vedanā, However, I think in this context, with Thero’s interpretation, it is more of Dukkha Vedana. In Saccavibhaṅgasutta, dukkha is also referred to as dukkha vedana:

Yaṁ kho, āvuso, kāyikaṁ dukkhaṁ kāyikaṁ asātaṁ kāyasamphassajaṁ dukkhaṁ asātaṁ vedayitaṁ – Physical pain, physical unpleasantness, the painful, unpleasant feeling that’s born from physical contact.

Also want to add a few more things to clarify:

We normally refer Jāti as the mundane, birth. But it seems like in this case the Jāti can refer to anything, even sights, viññana, vedana. In Jātidhammādisuttadasaka, we can see that all these things have jāti, jarā, byādhi, maranaṃ dhamma – liable to birth, decay, death. So it is possible that the jāti, jarā, byādhi, maranaṃ in the first noble truth also applies to these things, and not just the individual rebirth.

And for me it makes sense that these terms dont just apply to the individual because in the second line, it refers to everything: appiyehi sampayogopi dukkho, piyehi vippayogopi dukkho, yampicchaṁ na labhati tampi dukkhaṁ does not just refer to the self, but looks at all phenomenon in the world, which links better to the idea of Jāti of sights, viññana, vedana in the first line of the first noble truth.

pathfinder

ParticipantLal:

- In the first verse above “kusala-mūla paccayā saṅkhāra” is a contradiction. One cannot generate sankhara via kusala-mula.” Sankhara generation happens with akusala in mind.

- In the second verse above, it starts with Katame dhammā kusalā? and then to “tasmiṁ samaye avijjā paccayā saṅkhāro.” How can be kusalaassociated with “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāro“?

How can we resolve these contradictions? Isnt the Tipitaka self-consitent?

They also defined kusala-mūla paccayā saṅkhāra:

368.1Tattha katamo kusalamūlapaccayā saṅkhāro? 368.2Yācetanā sañcetanā sañcetayitattaṁ— 368.3ayaṁ vuccati“kusalamūlapaccayā saṅkhāro” …pe… 368.4tena vuccati“evametassa kevalassa dukkhakkhandhassa samudayo hotī”ti.

It looks like kusala mula involves sañcetanā, the cetana that extends rebirths, which is also kamma.

Lal: The confusion is to mix up puñña kamma with kusala kamma.

Does this mean that there can be mistakes in the tipitaka?

November 6, 2024 at 11:39 am in reply to: How to deal with abhijja, by Venerable deegoda dhammadassi #52648pathfinder

ParticipantLal: There is nothing to do except to eliminate avijja/moha from one’s mind. Then, the mind will automatically stop engaging in akusala kamma, including those three types done by the mind. It happens in a step-by-step process described by #3 above.

Doesnt the Buddha also encourage developing somethings? In Aparaaccharāsaṅghātavagga, he encourages developing Saddhindriyaṁ (faith), vīriyaṁ (effort) and a long list of other things to develop. In developing these things, pañña grows and avijja will automatically be removed. In Paṭhamavagga he also encourages:

“One thing, mendicants, when developed and cultivated, leads solely to disillusionment, dispassion, cessation, peace, insight, awakening, and extinguishment. – Buddhānussati.

In that case, is there still a Paticca Samuppada process for developing something good?

November 5, 2024 at 5:22 pm in reply to: How to deal with abhijja, by Venerable deegoda dhammadassi #52643pathfinder

ParticipantThank you for sharing, Amin, Hojan! It is a wonderful sermon. My key learning points are as follows

- He gives the analogy of a street fight between the good viññaṇa (created from Kusala Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda) and the bad viññaṇa from Akusala Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda. Our current bad habits are strong because the viññaṇa for them is strong, and to defeat it we need to 1) Starve the bad viññaṇa and 2) Feed the good viññaṇa by thinking about the dhamma. Such that when the stimulus comes up, we will chose to activate the Kusala Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda instead of Akusala one. He gives the example of YouTube addiction. When we sight/ thought of watching YouTube, the normal response would be to continue wanting to watch it (akusala PS), but with cultivation of good viññaṇa, we will activate the kusala PS and contemple for example, the anicca dukkha anatta nature of it.

I noticed in Kusala-Mula Paṭicca Samuppāda, the post needs to be re-written. Lal, would it be possible for you to rewrite this post?

- He gives another way of understanding PS, which is that even in every frame of the YouTube vid, there is a PS cycle where we have a vedana that we enjoy it, but also ends with jarā, marana, soka-paridēva-dukkha-dōmanassupāyasā sambhavan. However, we do not feel such suffering when watching because each successive frame is so quick. The suffering/ end of the PS cycle becomes obvious when the phone battery runs out suddenly.

I had another thought which is – what about feelings of satiation? For example, after eating food, we feel full and content, so where is the jarā, marana, soka-paridēva-dukkha-dōmanassupāyasā sambhavan? My response to that is that it is not very prominent becuase the more we eat, the fuller we get, the decrease in sukha vedana and tanha there is for every bite and the less delicious each bite gets, so the dhamma that we receive is less and less pleasureable, and in turn the suffering is less and less as we are more full. However all the while we are enjoying it, we are feeding the viññaṇa for indulging in food.

- He talks about the Vitakkasanthana sutta. at 1:03:55 He lists the ways to get rid of defiled thoughts in the following order:

- Thinking about the good qualities of Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha, Sila

- ādīnavo (looking at the negative side) – what do I lose if I engage in this action? what have I built up so far with my good practice that I will waste and restart my progress? what dukkha will I create?

- asatiamanasikāro (to ‘retreat’ or get out from the situation). Eg when my friend invites me to alcohol, I will excuse myself before it gets too tempting

- vitakkasaṅkhārasaṇṭhānaṁmanasikātabbaṁ (understand how it arises) Eg when I am trying to stop a cigarette addiction, I can see that every step of the way of going to the market and buying the cigarette is feeding the viññaṇa. Thus it is not enough to just say “stop smoking”, because that way I can be tempted to buy the cigarette and not smoke it, which will spiral to smoking. The viññaṇa should not be fed from the start

- Using external force to stop the thought. He suggests attadipatiya (thinking how it aligns to my own personality. I am a moral person, so is it fine for me to engage in this?), dhammadipatiya (the dhamma is well taught, is rarely found. It is a waste to engage in such action with this dhamma I have learnt), and lokadipatiya (that there are people in the world that would disapprove of my actions, eg unseen beings, ariya friends who would disapprove. I have not come across these terms attadipatiya, dhammadipatiya, and lokadipatiya but I think what the venerable mentioned is useful to stopping defiled thoughts.

2 users thanked author for this post.

pathfinder

ParticipantAre there other meanings for attā? If attā just means “a person” then this line wouldnt make sense:

“‘Cakkhu attā’ti yo vadeyya taṃ na upapajjāti. Cakkhussa uppādopi vayopi paññāyati.Yassa kho pana uppādopi vayopi paññāyati, ‘attā me uppajjāti ca veti cā’ti iccassa evamāgataṃ hoti. Tasmā taṃ na upapajjāti: ‘cakkhu attā’ti yo vadeyya. Iti cakkhu anattā.”

Loosely translated (using translation from the post earlier: “If anyone says, ‘The cakkhu is a person (attā),’ that is not tenable. An arising and disappearing of cakkhu (not the physical eye) is evident. If cakkhu is ‘self,’ that would imply: ‘my person (attā) arises and disappears’ That is why it cannot be argued that ‘The eye is person (attā).’ Thus cakkhu is ‘anattā’ (of no value)

And in this case, isnt the Buddha trying explain that things are not attā, but the opposite which is anattā? Which is why he uses these 2 words together to show contrast. That means that anattā should be linked to attā in some way.

pathfinder

ParticipantOh yes cubibobi, Lal, I talked about the absence of stand alone anatta without long ā that to contrast the statement here:

- ‘That is a critical conclusion that is related to “anattā.” It will also become clear that anattā differs from anatta (without the long “ā.”). Let us discuss anattā in detail now.’

which mean that at the very least, anattā should not differ from anatta, it is just another word form.

—

Although anattā should not refer to the sense of self, is it still useful to reflect that there is ultimately no ‘I’ or ‘self’ when processing vipaka, and that it is ultimately a mechanical process? I think discourses from Jethavanarama buddhist monastery focuses a lot on that.

pathfinder

ParticipantThank you!

On a side note, in “Pāli Dictionaries – Are They Reliable?“

Post: Grammar rules are bypassed in some cases. That is clear in verses “Buddhaṃ Saranam gacchāmi,” “Dhamman Saranam gacchāmi,” for example.

- There is no subject in the above verse. The first, of course, means, “I take refuge in the Buddha,” but “I” is missing in “Buddhaṃ Saranam gacchāmi.” It is just understood.

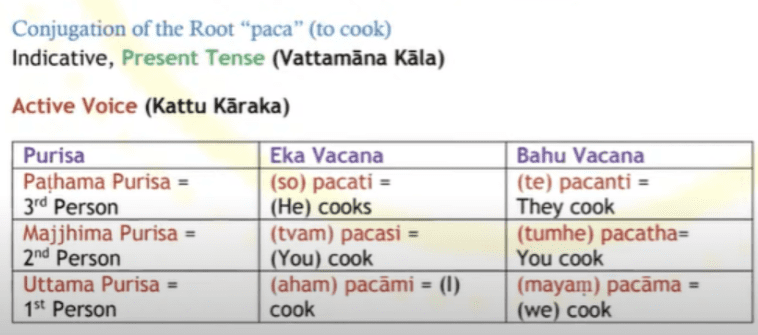

If I am not wrong, the I is included in gacchāmi, based on its conjugation, so it is not entirely necessary to add the pronoun ‘I’. In this case, a literal translation would be: ‘Buddha, the Refuge (Saranṃ), (I) go to (gacchāmi)’

I have attached a conjugation table for reference, each word can be conjugated differently based on the pronoun.

This is similar to Passāmi loke sadhane manusse – (I) see rich people in the world, in Raṭṭhapālasutta where the I is not included.

This is my understanding of reflected languages as well, eg spanish, french. And only based on my basic understanding of Pāli! Please feel free to correct me, I have only started learning.

pathfinder

ParticipantLal: My point was that the merits of giving depend on the giver’s mindset. I think the sutta also tried to convey that idea in the context of that sutta.

Yep! So here we actually find a contradiction between grammatical analysis and actual meaning. Do you take into account grammar when looking at suttas?

pathfinder

ParticipantIt does change the meaning! The sentence becomes ‘giving a gift of mental adornation and mental pre-requisites’ instead of ‘with a pre-requisite of a clear mind’. Meaning ‘we should give dhamma’ instead of previous interpretation ‘we should give with a clear mind’

ChatGPT:

- Current grammatical structure: It suggests that “mental adornments and requisites” are what is being given as the object of dāna.

- Your interpretation (“with a prerequisite of a decorated mind”): For this meaning, the compound would need to be in the instrumental case to show that these adornments are a condition for the giving, not the object itself.

I know ChatGPT’s interpretation is less in line with the whole sutta, but grammatically it is more accurate

pathfinder

ParticipantI asked ChatGPT:

parikkhāra means more like “pre-requisite.”<br />

P.S. “Prerequisite” emphasizes a preceding condition or order, whereas “Requisite” speaks to the fundamental necessity of something.<br />

2. Thus, “api ca kho cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ dānaṁ deti” conveys the idea: “instead (compared to the dāna in the previous verses), with a “cleansed mind.”<br />

Literally, it can mean “With a pre-requisite of a decorated mind”.Do you think this makes grammatical sense?

ChatGPT:

Your interpretation, “with a pre-requisite of a decorated mind”, for “api ca kho cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ dānaṁ deti”, raises an interesting perspective, but there are some grammatical considerations that need to be examined.

Grammatical Considerations:

- Compound Structure:<br />

The compound “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ” is in the accusative singular form (as indicated by the ending -aṁ). In Pali, the accusative case is typically used for the direct object of the verb. In this sentence, it seems like it functions as the object of the verb “deti” (to give). So, grammatically, it is the “mental adornments and mental requisites” that are being given (as part of the dāna).<br />

For your interpretation to mean “with a prerequisite of a decorated mind,” you would expect “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ” to be in the instrumental case (which conveys accompaniment or means). The instrumental case (e.g., “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhārena”) would suggest the idea of “with” or “by means of” something, which would be more appropriate for expressing a condition like a “prerequisite.” - Use of “Api ca kho”:

- “Api ca kho” introduces the sentence with emphasis. It suggests that what follows is an important point or something being added to what was previously mentioned, and often sets up a contrast or continuation. This supports the idea of the phrase contrasting with something before (e.g., a different kind of dāna).

- Meaning of “Parikkhāra”:

- As you pointed out, “parikkhāra” can carry the sense of “prerequisite” or “necessary equipment”. It refers to something essential that prepares or furnishes the mind, aligning with your idea of a “prerequisite” for a cleansed or decorated mind.

- “Deti” (to give):

- The verb “deti” makes “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ” the object of what is being given. If we follow strict Pali grammar, this suggests that what is being given is the “mental adornments and requisites” themselves, not that they are a condition for the act of giving.

Alternative Reading for Your Interpretation:

If you want the phrase to mean “with a prerequisite of a decorated mind”, the compound “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ” would ideally be in the instrumental case as mentioned earlier, like “cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhārena”. This would clearly mark the phrase as a condition or accompaniment rather than the object of the verb.

Does it make grammatical sense?

In its current form, “api ca kho cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ dānaṁ deti” makes grammatical sense in Pali as “he/she gives a gift of mental adornments and mental requisites.” However, for your interpretation of “with a prerequisite of a decorated mind” to work, the phrase would need to use the instrumental case to indicate that the “mental adornments and requisites” are a prerequisite for giving, rather than what is being given.

Summary:

- Current grammatical structure: It suggests that “mental adornments and requisites” are what is being given as the object of dāna.

- Your interpretation (“with a prerequisite of a decorated mind”): For this meaning, the compound would need to be in the instrumental case to show that these adornments are a condition for the giving, not the object itself.

So while the idea of your interpretation is insightful, it requires a change in case to align grammatically with that meaning.

—

The grammatical analysis makes sense to me, but it is only based on my basic understanding of Pali from youtube. Do you agree with it? And do you think it is important to take into account the grammar of the words when translating it?<br />

<br />

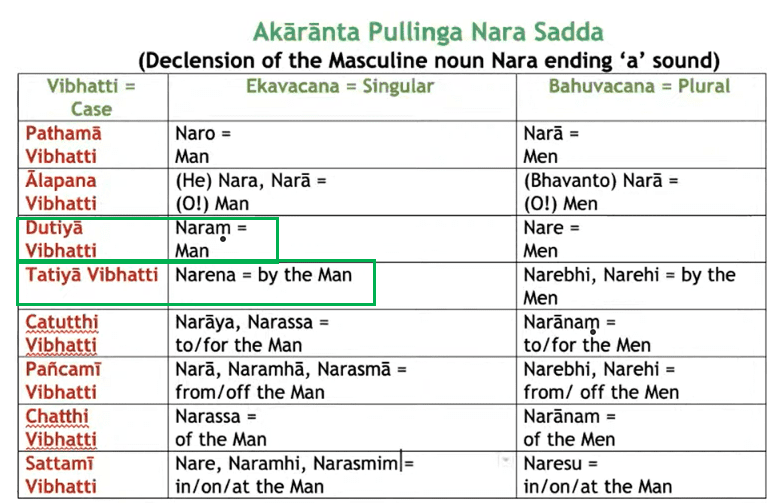

For reference, the word cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ ends with aṁ, which makes it an object. <br />

Dutiyā Vibatthi (Object, Accusative), eg (Buddho dhammaṃ deseti) – The Buddha (subject) gives (verb) Dhamma (object)<br />

So ‘api ca kho cittālaṅkāracittaparikkhāraṁ dānaṁ deti’ means he/she gives a gift of mental adornments and mental requisites (object)<br />

<br />

Chat GPT is arguing that it should be Tatiyā Vibatthi (By/ through/ with), eg ahaṃ (I) hatthena (by the/with the hand) likhāmi (write)- I write by the/ with the hand. If we want to stick to the intrepretation of ‘he gives with a clear mind’ -

AuthorPosts