December 14, 2019; revised November 26, 2022

Summary of Discussion Up To Now

1. In the subsection “Worldview of the Buddha,” we discuss how the Buddha explained the sensory experience. More importantly, the Buddha taught how a “living being” generates kammic energies for future existences (bhava) based on “attachment” (taṇhā) to a given sensory experience. As we have discussed, “attachment” can happen due to greed, hate, or an unwise mindset.

- First, we discussed how a sensory event starts when a ārammana (sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, dhammā) comes to the mind when one of the six senses (internal āyatana) comes into contact with an external āyatana. Becoming aware of sensory input is one of the six types of vipāka viññāṇa: “cakkhu viññāṇa, sōta viññāṇa, ghāna viññāṇa, jivhā viññāṇa, kāya viññāṇa, manō viññāṇa.”

- Those six types of viññāṇa are vipāka viññāṇa. They DO NOT generate kammic energy. They are “experiences.”

- As we will see, kamma viññāṇa can only be manō viññāṇa. Thus, some manō viññāṇa are vipāka viññāṇa and others are kamma viññāṇa.

2. Then, one MAY “attach to” or “get stuck in” that sensory experience INSTANTLY. That means generating taṇhā. Then the “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step automatically follows. That is a step in the middle of the Paṭicca Samuppāda (PS) cycle.

- One will attach (taṇhā) only if one has “defiled gati.” That means one likes or dislikes that sensory experience (which could be connected with ignorance too.) If one attaches, then one will start thinking and speaking (with vaci saṅkhāra) and even may take actions (with kāya saṅkhāra) with a DEFILED MIND. That means those saṅkhāra arise via “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra.” That is part of “upādāna” or “pulling that ārammana close.”

- Therefore, what we summarized here in #2 is how the “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step in PS initiates a new PS process that starts at “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra.” That is how the PS cycle begins in real life, beginning with a ārammana (as detailed in the Chachakka Sutta (MN 148).

Summary in Charts

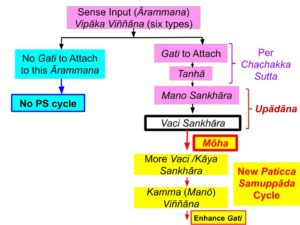

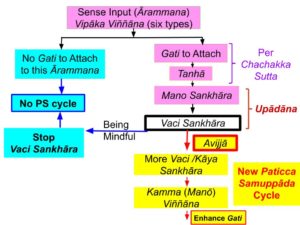

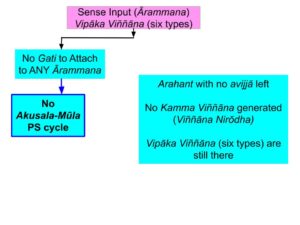

3. Since it is CRITICAL to understand what we discussed above, I have made the charts below to help us with the discussion.

One can download the charts for easy reading/printing: “Response to a ārammana with Mōha,” “Response to a ārammana with Avijjā,” and “Response to a ārammana by an Arahant.“

- Paṭicca Samuppāda referred to in ALL the above charts is the “Akusala-Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda.” That PS process leads to future suffering.

- Therefore, saṅkhārās that do not arise in an Arahant are ONLY “bad or immoral saṅkhārā,” i.e., abisaṅkhārā. An Arahant will still generate manō, vaci, and kāya saṅkhāra to think, speak, and take action. He/she will be engaged in “puñña kriyā” or “moral deeds.” Such “moral deeds” are NOT “puñña abhisaṅkhāra” because one does them with complete comprehension of the anicca nature. We will discuss this critical point later.

Difference Between Mōha and Avijjā

4. Let us start with the chart on the left. That chart is for an extreme case of a “totally morally-blind” person. That mind is covered with defilements (mōha.) Just like an animal, such a person would go along with any temptation that comes to mind. His/her “bad gati” will only get stronger.

- The chart in the middle applies to a wide range of humans with avijjā. Avijjā is a lower form of mōha. When one removes the ten types of micchā diṭṭhi, mōha reduces to the avijjā level. Any human who knows right from wrong is an average human. It also includes those who are Ariyā (Sōtapanna Anugāmi and above) but have not yet attained Arahanthood.

- Of course, any Ariya (Noble Person) is INCAPABLE of doing apāyagāmi deeds. An Anāgāmi is INCAPABLE of craving for sensual pleasures, etc. Therefore, as one moves to the higher stages of Nibbāna, one will “attach to” less and less ārammana (sensory inputs.)

- But any average human — no matter how “moral” by conventional standards — is CAPABLE of doing even an apāyagāmi deed. The ārammana must be strong enough to be tempted.

- An Arahant has a totally-purified mind and has no “bad gati” left. Therefore, he/she WILL NOT initiate an “Akusala-Mūla Paṭicca Samuppāda” cycle under ANY circumstance. That is indicated in the third chart.

Difference Between Vipāka Viññāṇa and Kamma Viññāṇa

5. Above charts also help us clarify the difference between vipāka viññāṇa and kamma viññāṇa. Any sensory EXPERIENCE is a vipāka viññāṇa. Vipāka viññāṇa can come in through any of the six sense faculties, as shown at the top of the charts. Every living being, including an Arahant, experiences vipāka viññāṇa. In other words, ANY sentient being can see, hear, etc.

- If one attaches (taṇhā) to a ārammana, then that initiates the step “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step in PS. That means one starts “pulling that ārammana close (upādāna).” First, one starts thinking about it with vaci saṅkhāra. One does that with the sense of a “me” involved in the sensory experience. As we have discussed, there is no need for a “me” or a “self” to experience a sensory input. See “Chachakka Sutta – No “Self” in Initial Sensory Experience.”

- Therefore, at the beginning of that “taṇhā paccayā upādāna” step, one starts generating saṅkhāra about that ārammana with the “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” step in PS. That is when a PS cycle begins at the “beginning” and then runs through the end.

- The next step in PS after the “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra” step is “saṅkhāra paccayā viññāṇa.” That viññāṇa is a kamma viññāṇa. Since it arises ONLY in mind, that is a manō viññāṇa. This kamma viññāṇa appears at the bottom of the FIRST TWO charts. An Arahant does not generate kamma viññāṇa. Therefore, kamma viññāṇa is absent in the third chart.

Kamma Viññāṇa Generated with the View and saññā (Perception) of “Me” or a “Self”

6. From the last bullet of #5, it is clear that one’s mind will NOT go through the Akusala-Mūla PS at ANY TIME, only if one is an Arahant.

- That is because it is ONLY an Arahant who would have “seen” the futility of attaching to ANY sensory input (ārammana.) There is no sense of a “me” or a “self” in an Arahant.

- That is a point that we will discuss in detail in upcoming posts. But it is good to know about that point ahead of time. It is CRITICAL to understand the material presented so far to “keep up” with the upcoming posts when we discuss sakkāya diṭṭhi.

- As we can see, ANYONE below the Arahant stage WILL attach to at least a few sensory inputs. That is because anyone below the Arahant will have at least a trace of avijjā anusaya left.

- It is impossible for an average human even to comprehend that. That is why the Buddha emphasized that it is incorrect to say that a “self” does not exist. The point is that for ANYONE below the Arahant stage of Nibbāna, a “self” with “gati” exists!

- However, anyone above the Sōtapanna Anugāmi can “see” that it is unfruitful to take anything in this world to be “mine,” and it can lead to future suffering. That “seeing” is “with wisdom” and is lōkuttara (or lōkuttara) Sammā Diṭṭhi. A fish biting the tasty bait on a hook does not “see” that it will suffer so much. Like that, an average human cannot “see” the suffering hidden in sensual pleasures. We will discuss details in future posts.

- One becomes a Sōtapanna Anugāmi when one comprehends Tilakkhana (anicca, dukkha, anatta) at least to some extent. Even after that, the saññā (perception) of a “me” will be there. That perception will reduce with higher stages of magga phala and disappear at the Arahant stage.

Starting with a “Self” or “No-Self” is not the correct approach

7. As we summarized in #5 above (and discussed in the post mentioned there), attachment to a ārammana happens instantly. That requires no conscious thinking and thus is NOT possible to stop. As long as one has “bad gati,” one MAY attach to some sensory inputs (ārammana.)

- The way to eliminate taṇhā is to reduce and finally remove one’s “bad gati.” Luckily, humans have the ABILITY to do that by understanding the PS process.

- Indeed, there is a “self” is in the PS process. However, that is not an unchanging “self” like a “soul” or a “ātma.” I call it a “dynamic self,” see “What Reincarnates? – Concept of a Lifestream.” That “self” disappears when one attains the Arahant stage!

8. Therefore, until one becomes an Arahant, a sense of “self” will decide how to respond to sensory input based on some attachment to “this world.” As shown in the middle chart above, anyone can stop any “bad vaci saṅkhāra” that arises when tempted by a given sensory input. If that fails, one can stop kāya saṅkhāra, which leads to physical actions. Simply put, one should stop immoral conscious thoughts, speech, or deeds as soon as one becomes aware of them.

- When one becomes a Sōtapanna Anugāmi by comprehending Tilakkhana to some extent, one’s “apāyagāmi gati” will disappear.

- Until then, one can practice Ānāpānasati or Satipaṭṭhāna Bhāvanā to stop some temptations. One does not need to have formal meditation sessions. It is utterly useless to have formal meditation sessions and not to act with mindfulness when one goes through daily activities. That is when one generates most of the defiled thoughts and actions.

- Formal meditations become more relevant after getting to the Sōtapanna stage. That is why “bhāvanāya pahātabbā” comes last in the Sabbāsava Sutta (MN 2). There, “dassanena pahātabbā” of “removal via correct vision” is first on that list. That is the “correct vision” required to be a Sōtapanna. One must first understand what to meditate on!

Kamma Viññāṇa Have Future Expectations

9. What is the real difference between a vipāka viññāṇa and a kamma viññāṇa?

- Vipāka viññāṇa provides the sensory experience. One sees with cakkhu viññāṇa, hears with sōta viññāṇa, tastes with jivha viññāṇa, smells with ghana viññāṇa, feels touch with kāya viññāṇa, and thoughts coming to the mind with manō viññāṇa.

- Kamma viññāṇa arise via “avijjā paccayā saṅkhāra.” For example, when one gets attached to a ārammana via greed or hate, one has an EXPECTATION. If one likes the ārammana, one wants more of it. If one dislikes it, one wants it to go away. Either way, there is an expectation.

- Thus when one consciously thinks (vaci saṅkhāra) and takes actions (kāya saṅkhāra), there are “expectations” embedded in such saṅkhāra. Those saṅkhārā lead to kamma viññāṇa via “saṅkhāra paccayā viññāṇa.”

10. Those “expectations” in kamma viññāṇa are energies generated by the mind in javana citta. They stay “out there in the world” as dhammā. Those are part of the dhammā in “manañca paṭicca dhammē ca uppajjāti manō viññāṇaṃ.”

- Therefore, just like the other five types of rūpa are “out there in the world,” dhammā are “out there,” too. They can be detected by the mana indriya, just like a sound detected by the sōta indriya. That is how our future expectations periodically come back to our minds, i.e., how we remember our plans for the future. Sigmund Freud called that the “subconscious.” Of course, he had no idea about the actual mechanism.

- Dhammās are rūpa too. But they are just energies that are below suddhāṭṭhaka. They are “anidassanaṃ appaṭighaṃ dhammāyatanapariyāpannaṃ.” They “cannot be seen or touched.” See, “What are Rūpa? – Dhammā are Rūpa too!“

- The other five types of rūpa sensed via the five physical sense faculties are above the suddhāṭṭhaka level. Modern science is only aware of those five types.

- We will discuss dhammā in detail in the next post.

All posts on the new series at “Origin of Life.”