- This topic has 8 replies, 4 voices, and was last updated 3 months ago by

Jittananto.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

November 3, 2025 at 11:55 am #55522

DhammaSponge

ParticipantGiven that this channel was recommended to me on this website for a source of dhamma talks, I am still working with the “deeper meanings” of Tilakkhana, as it is put here.

Anicca, tersely defined, is the inability to keep things as we like. The “deeper meaning,” per the video, is that the “natural order” of nature is chaos. Things that seem ordered to us (even though there isn’t intrinsically a right or a wrong order in the grand scheme of things) will tend towards disorder, as per the second law of thermodynamics. We could thus think of icca as an expectation that things can and ought to be always ordered a certain away, as opposed to the countless microstate configurations available in disorder. We could also think about nicca as our tendency to fix objects as static entities, while anicca emphasizes that all configurations of rupa are non-fixed processes subject to cause and effect.

Dukkha, tersely defined, is that there is a hidden suffering in things that we see as pleasure. The video proposes that dukkha is actually an extension of the second law of thermodynamics: if order is to be maintained in the way we like it, work must be expended to maintain it. We create objects or configurations of rupa, for example, because there is a necessity for these things. But necessity, per the Bhante, is rooted in ignorance, and that is why the object not only exists, but can also exist in many subtle variations for the enjoyment of the six sense bases.

Anatta, tersely defined, is the helplessness through the rebirth process if one is to view objects as nicca and sukkha nature. Now, I know that it has been emphasized multiple times here that anatta is not about simply “no self,” yet it is regardless emphasized by the Bhante that although there isn’t a true self, the sense of a self still exists. Since all five aggregates exist- be it on the scale of seconds or eons- to fulfil a necessity (dukkha), the sense of self is no different. To fulfill the need of continual existence, the mind performs abisankhara and creates the sense of a self, in the same sense that a woman that miscarried continues taking care of her child even though it no longer exists.

I guess what is meant is that this dynamically changing sense of self exists more or less until Arahanthood, and that’s why it is worth considering that considering the five clinging aggregates are not “me” or “mine.”

Thoughts?

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

November 3, 2025 at 7:39 pm #55525

Jittananto

ParticipantSādhu Sādhu Sādhu 🙏🏿🙏🏿🙏🏿 Is very well explained, my friend !

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

November 4, 2025 at 10:48 am #55529

Jaro

ParticipantI believe this is a legitimate way to understand Anicca. Order and chaos are not intrinsic properties of any object. In physics, we describe disorder in terms of entropy: a gas has higher entropy than a liquid, and a liquid has higher entropy than a solid. Yet none of these states is inherently “better” or “worse.” They simply arise from different causes and conditions — that’s it.

There are many ways to contemplate Anicca:

- Everything unfolds according to cause and effect, not according to our wishes.

- The nature of the world cannot fulfill the desires we direct towards it.

- Think of a desert, a sandcastle, a dry bone, or a pile of garbage.

What matters most is that Anicca always carries with it a tone of frustration and stress, because our desires are inevitably disappointed over time.

There are three categories of Dukkha, all of which describe forms of suffering that can be eliminated by relinquishing attachment to worldly things:

- Dukkha-Dukkha: Immediate suffering that arises as the direct consequence of harmful actions.

- Viparinama-Dukkha: The pain that comes when something precious inevitably comes to an end.

- Sankhara-Dukkha: The ceaseless effort and strain we invest in trying to recreate the causes and conditions of pleasure.

Among these, Sankhara-Dukkha is considered the most dangerous form of suffering.

Anatta also carries a range of interpretations, depending on context. It can mean:

- The unsubstantial nature of worldly pleasure — once it’s over, nothing remains but a fading memory.

- The absence of refuge in the world — where there is suffering, there can be no safety.

- The futility of all efforts to find lasting fulfillment within this world.

Ultimately, the Three Marks of Existence serve as arguments for gradually diminishing our attachment to worldly pleasures until it finally disappears altogether.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

November 4, 2025 at 11:55 am #55530

Lal

KeymasterJaro wrote: “Sankhara-Dukkha: The ceaseless effort and strain we invest in trying to recreate the causes and conditions of pleasure. – Among these, Sankhara-Dukkha is considered the most dangerous form of suffering.”

- Yes. Sankhara-Dukkha applies to every sensory input for a puthujjana.

- The mind of a puthujjana gets into the kama loka with any sensory input and at least generates kama sankappa in the ‘purana kamma‘ stage. Even if the mind does not proceed to the ‘nava kamma‘ stage, subtle/weak kamma are done with kama sankappa.

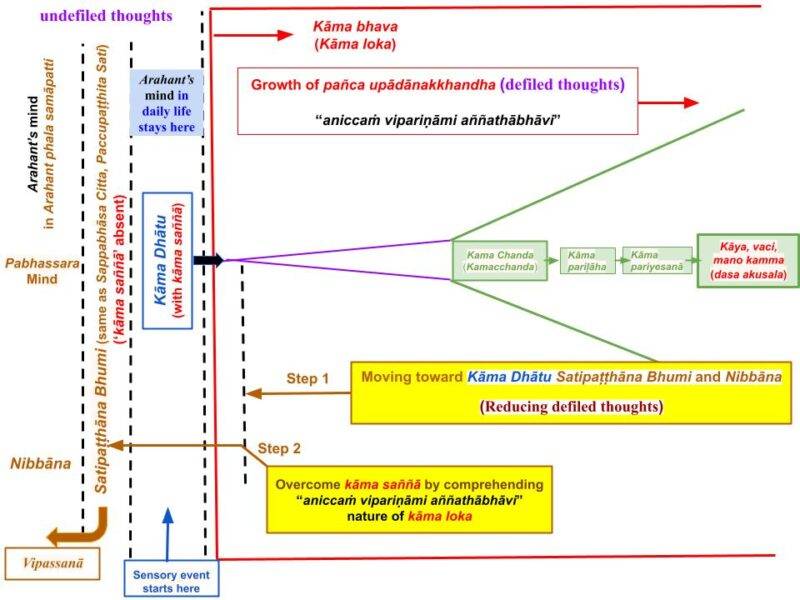

- That is a clear expression of ‘anicca nature’ and can be seen in the following chart.

- “Aniccaṁ vipariṇāmi aññathābhāvi” nature is associated with all sensory inputs for a puthujjana.

- If one comprehends that fact, one can become a Sotapanna Anugami.

- I discussed that in several posts. For example, “Sotapanna Anugāmi and Anicca/Viparināmi Nature of a Defiled Mind” and “First Stage of Ānāpānasati – Seeing the Anicca Nature of ‘Kāya’ .”

P.S. It is called Sankhara-Dukkha because of the ‘sankhara generation’ in panupadanakkhandha accumulation (or equivalently, the initiation of Paticca Samuppada process.)

- “Avijja paccaya sankhara” is how kamma accumulation (a Paticca Samuppada process) starts.

- That starts automatically in the ‘purana kamma‘ stage with the automatic generation of kama sankappa.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

November 4, 2025 at 3:34 pm #55539

Jaro

ParticipantLal, you wrote that the mind of a Puthujjana is ALWAYS moving in the direction of vipariṇāma. So, essentially, their minds can only become more and more defiled.

This means that an ordinary person, a Puthujjana, is swept away by the flood and has no real power to resist it. They lack the means to fight against it, for they have no understanding of the Tilakkhana, the Noble Truths, or the process of rebirth.

But what about a Sotāpanna—or someone who at least knows the Dhamma and strives to put it into practice (Saddhānusārī or Dhammānusārī)—when they find themselves in a Nava Kamma stage?

If I understand correctly, such a person would apply the Dhamma. They would contemplate the nature of anicca, dukkha, and anatta and use that understanding to push back against the current. In doing so, they move away from “Aniccaṁ vipariṇāmi aññathābhāvi” and direct their mind toward Nibbāna.

-

November 4, 2025 at 4:27 pm #55540

Lal

KeymasterMoving to the ‘purana kamma‘ stage happens depending on the number of samyojana that remain intact. In the following, we will consider a human in kama loka.

- A puthujjana enters the ‘purana kamma‘ stage with all ten samyojana intact. Thus, the likelihood of getting to the ‘nava kamma‘ stage is high.

- A Sotapanna enters the ‘purana kamma‘ stage with seven samyojana intact. Thus, a Sotapanna’s mind will still move in the “Aniccaṁ vipariṇāmi aññathābhāvi” direction. However, the likelihood of reaching the ‘nava kamma‘ stage is lower, since he has three fewer samyojana intact. A Sotapanna’s mind does not attach with the three ditthi samyojana (i.e., with ‘wrong views’). That is why a Sotapanna is incapable of doing ‘apayagami kamma.’

- An Anagami will not enter the ‘purana kamma‘ stage even though he has five samyojana intact. An Anagami has eliminated the five samyojana that bind one to the kama loka; therefore, he will not generate ‘kama sankkappa‘ to attach to the ‘kama sanna‘ in the ‘kama dhatu‘ stage. Thus, an Anagami‘s mind will stay in the ‘kama dhatu‘ stage. See, for example, “Upaya and Upādāna – Two Stages of Attachment.”

- The above statements (for an Anagami) also hold for an Arahant, of course. In addition, an Arahant‘s mind will not enter rupa loka or arupa loka either, since it has eliminated all ten samyojana. See “Loka and Nibbāna (Aloka) – Complete Overview.”

I recommend reading those posts carefully. Feel free to ask questions. This is what is needed to become a Sotapanna.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

November 5, 2025 at 4:41 am #55545

Jaro

ParticipantWhat about a non-ariya individual who has learned the Buddha’s teachings — someone positioned between a puthujjana and a sotāpanna anugāmi?

You mentioned that such a person automatically enters the pūrana kamma stage but can stop the nava kamma stage through mindfulness.

Does this mean that, by being mindful, they can effectively avoid drifting further toward “Aniccaṁ vipariṇāmi aññathābhāvi”?

-

November 5, 2025 at 6:59 am #55548

Lal

KeymasterAnyone who is not an Ariya (at least a Sotapanna Anugami) is a puthujjana. So, most of the ‘Buddhists’ today are probably puthujjana, because they are not at least Sotapanna Anugami. But they are likely to be more ‘moral’ compared to others.

- Even for a puthujjana, not all sensory inputs lead the mind to the nava kamma stage. Most of the things we encounter (for example, looking out of the window while riding a bus) do not lead the mind to attach to them. Those sensory events stop at the pūrana kamma stage even for a puthujjana.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

November 5, 2025 at 10:14 am #55550

Jittananto

ParticipantOne thing is certain: we need the ten paramis and merits to become Ariyas, Jaro. All Ariyas were puthujjanas in this endless Samsara. The great disciples of Lord Buddha and the Lord himself overcame, with strength and difficulty, the nava kamma that confronted them. The Great Venerable Maha Mogallana killed his parents (anantariya papa kamma) in a past life.A puthujjana with merits and powerful paramis can endure for a very long time, even several lifetimes, but a long time does not mean being free forever.

Sooner or later, even the greatest Bodhisattas are overwhelmed by the Nava Kamma and end up committing akusalas actions. The yogi Harita (who was our Bodhisatta) had developed jhanas and abhinnas but ultimately ended up sleeping with the king’s wife, who supported him. However, he recovered and decided to return to live in the mountains to regain his jhanas. His action was immoral, but it didn’t prevent him from continuing his journey to Buddhahood. This is why the Khanti Paramis (Patience) and the Viriya Paramis (effort) are so important (all the Paramis are important). See Pāramitā – How a Puthujjana Becomes a Buddha They allow us not to abandon our journey to Nibbana, and even if we fall, we get back up to continue. A one-month-old baby will never become a physics professor. However, one day this child will grow up, become an adult, and learn physics to become one. We must always observe the law of cause and effect. Being Ariya is an effect, and the causes for achieving it are difficult. Being a puthujjana is an effect, and causes maintain this state.

Hētum Paṭicca Sambhūtam Hētu Bhamgā Nirujjati. It means: “When causes come together, an effect manifests. When the causes cease, the effect disappears.”

The Venerable Sariputta and Maha Mogallana became sotāpanna by briefly contemplating the law of cause and effect. This is the verse they contemplate:

Ye dhamma hetuppa bhava

tesam hetum tathagato aha

tesanca yo nirodho

evam vadi maha samano.

It means: The Tathagata has declared the cause and also the cessation of all effects which arise from a cause. This is the doctrine held by the Great Samana.

What keeps a being in the lineage of the puthujjanas? It is the first three saṁyojanas (Silabbata paramasa, Vicikicca and Sakkaya ditthi). These are the causes that must be eliminated. One cannot do anything against the effect. All these yogis only address the effect of Nava kamma by entering the jhānas, but they do not eliminate Kāma ragā, which is the cause. If one wants to achieve the Ariya effect, one must combine the causes, which are the understanding of natural laws (Anicca, Dukkha, and Anatta) and the daily practice of the Dhamma.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.